… this site is still under construction! …

Coming to Los Angeles we are not only leaving Europe but we will also move to the 20th century: we consider the turn in the city’s mobility system from rail and streetcar to the automobile as the most prominent one sustainably shaping her urban form towards extreme sprawl.

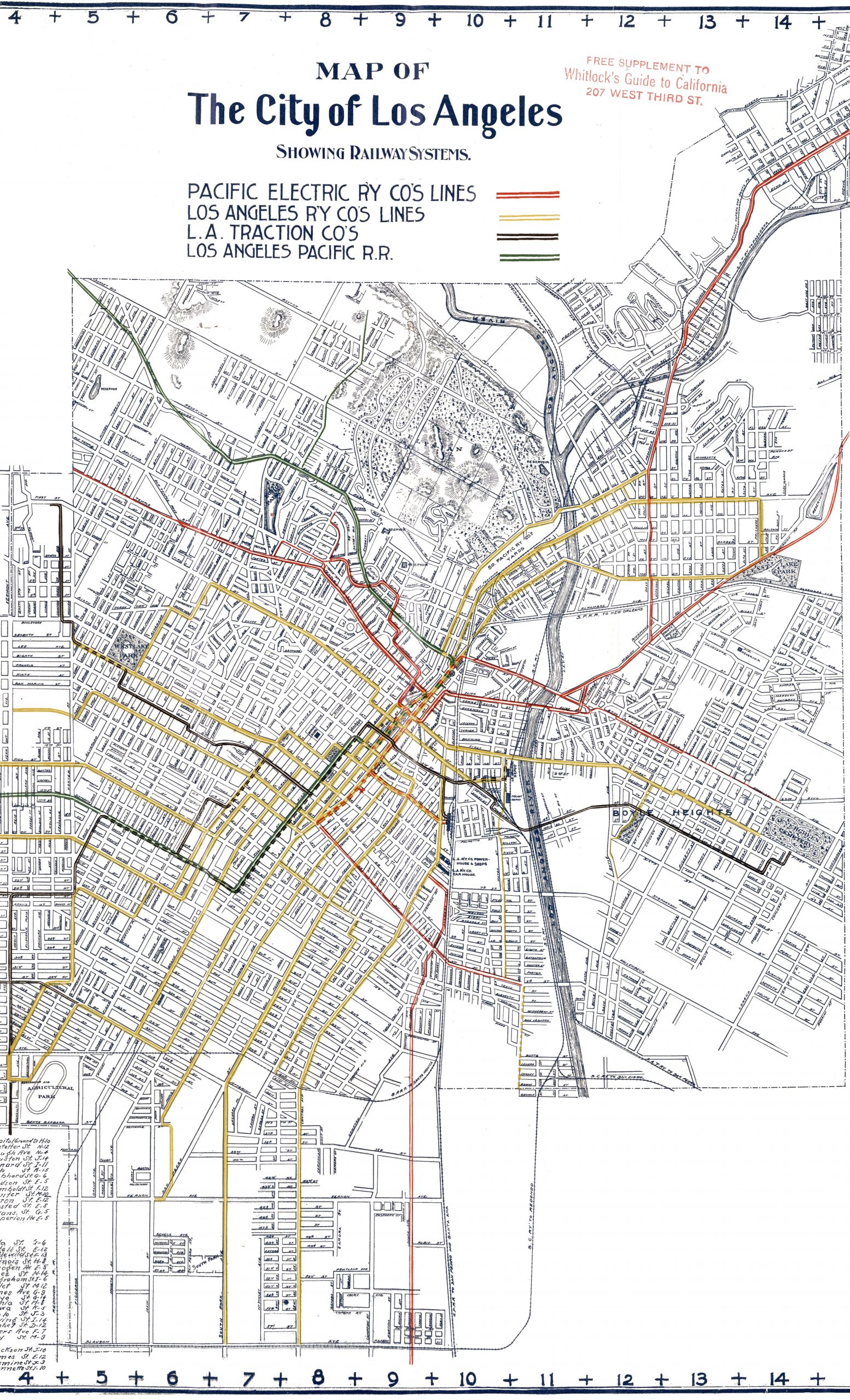

That LA is the Motown in the world is well known. That it had one of the largest intraurban rail and streetcar systems in the early years of the 20th centrury may be lesser known.

How did Los Angeles become a city where cars are the defining feature of urban life? How did that transformation come about?

In the following I am referring to the book “Los Angeles and the Automobile” by Scott Bottles which tries to answer this question for LA, one of the most car-centric cities in the US. Brian Potter has summarized the book in a paper published by Construction Physics in 2023. Most of the following paragraphs are taken from this paper (in italic) – with some adaptions and additions. All maps and grafics are from my searches in various archives, especially the David Rumsay Map Collection, Los Angesles Public Library and Los Angeles Historical Photos from Water and Power Accociates.

Brian Potter describes this fundamental turning point in LA’s urban development:

Over a period of less than 30 years, Los Angeles was transformed from a city with streetcar and train-based transportation to one where the car reigned supreme.

LAs special urban development history

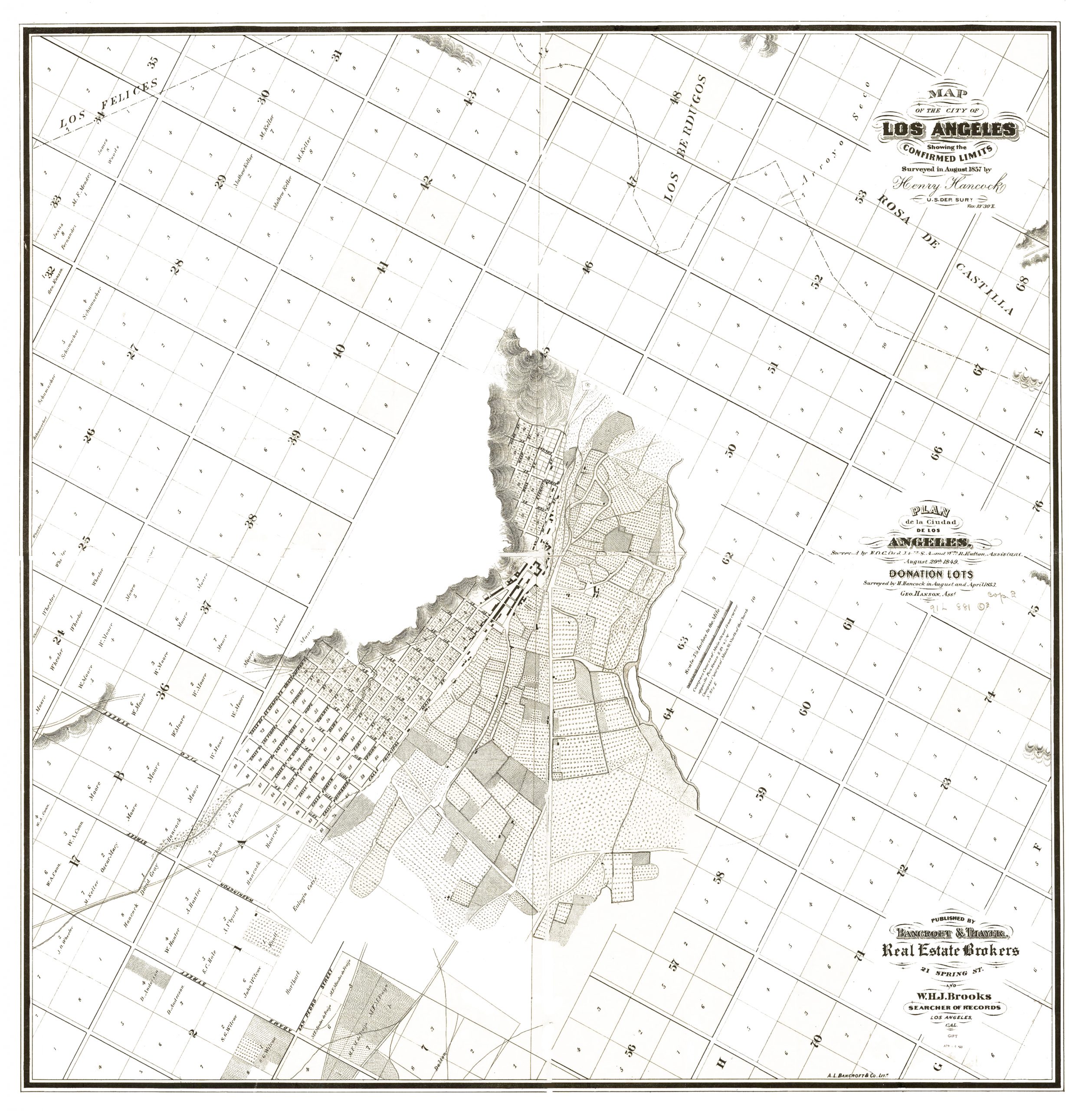

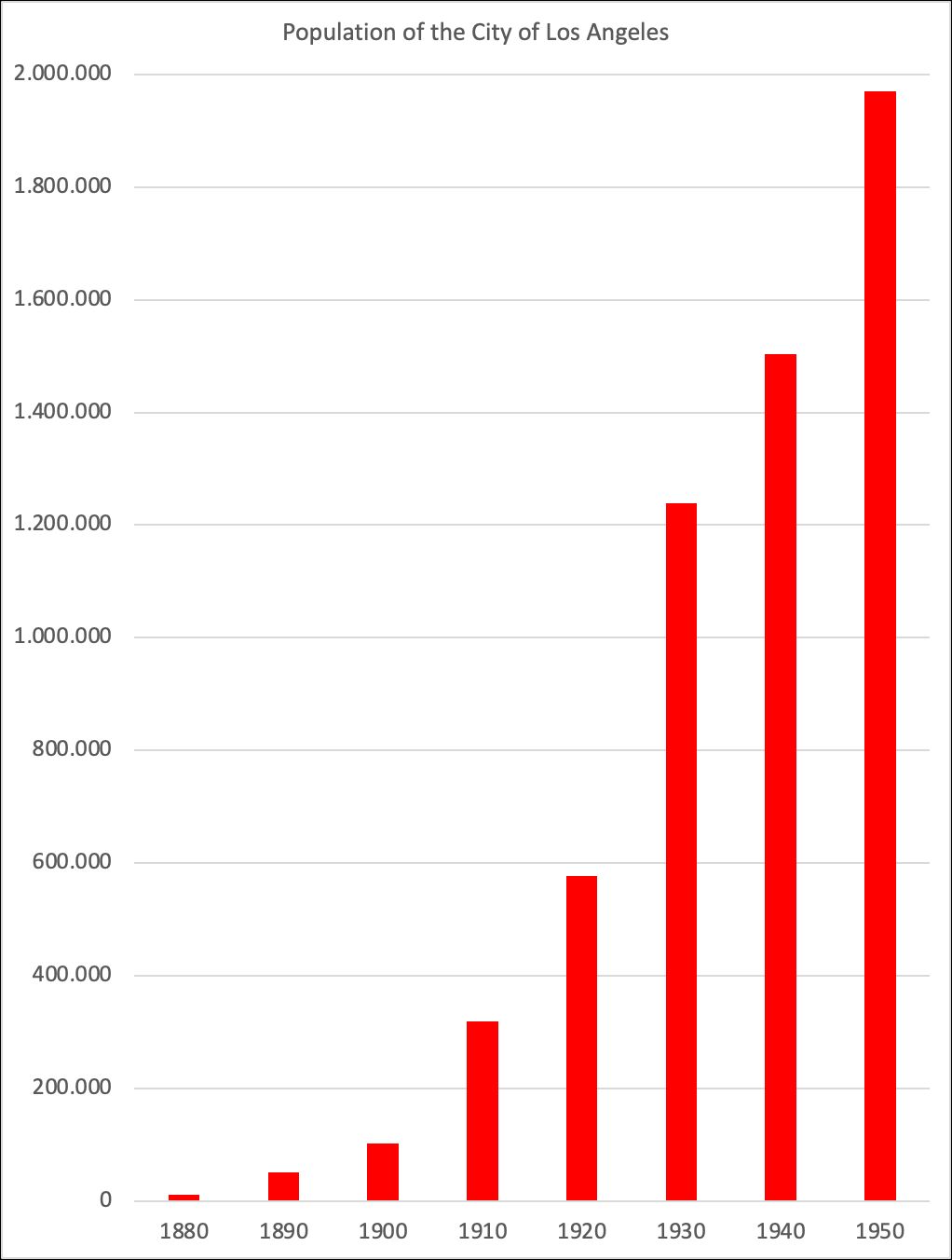

First founded in 1781, Los Angeles was a small city through the 19th century. As late as 1880 the city had only 11,000 people, compared to almost 2 million in New York and over half a million in Chicago.

At that time european cities looked like this: Vienna in 1843, Munich in 1849, London in 18…

But the city began to grow rapidly after the Southern Pacific Railroad connected it with the rest of the country in 1876. Between 1880 and 1930, LA grew on average around 10% per year, and from 1890 to 1930, when it hit 1.2 million inhabitants,

By 1909 Los Angeles had developed to a veritable city with a pretty compact city core as can be seen in this well designed bird’s view:

Los Angeles 1909 by Gates, Worthington Western Litho Birdseye View Publishing Co. Source: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA dcu

At this Point you may wish to have a look at the astonishing spacial expansion of Los Angeles Region as depicted on ESRI’s The Age of Megacities site, which we have mentioned in our chapter Physical Development of Cities:

Largest Rail and Streetcar System

LA was the fastest growing city in the US. Unlike East Coast cities, Los Angeles was never a true “walking city.“ It grew hand in hand with the electric railway, and by 1910 boasted an extensive local streetcar system (which operated within the city).

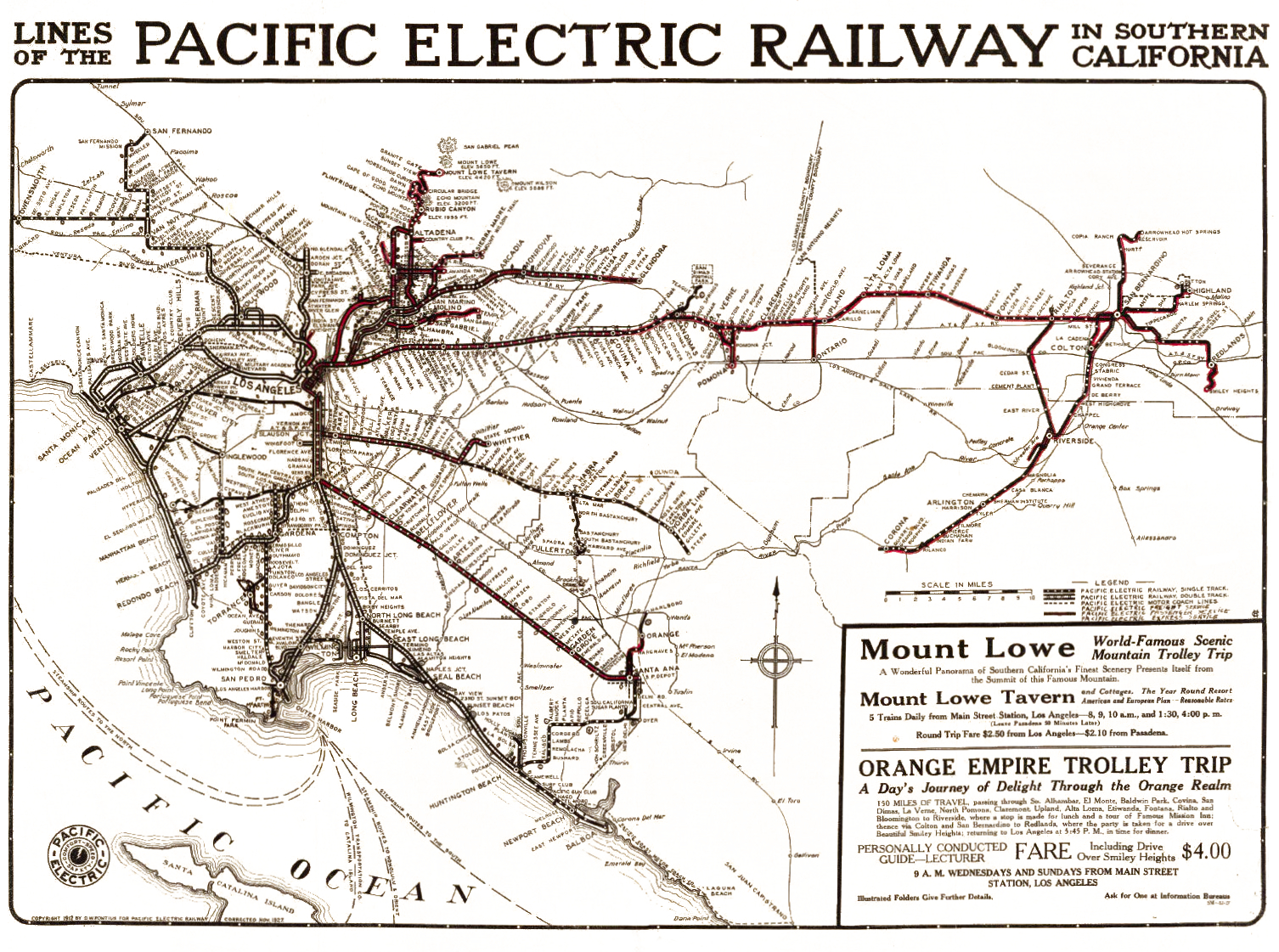

The map below shows the extensive rail and streetcar system as early as 1903.

Five years later it had been further enlarged to the West and South. Circles from Down Town show the extend to which streetcars serve the city.

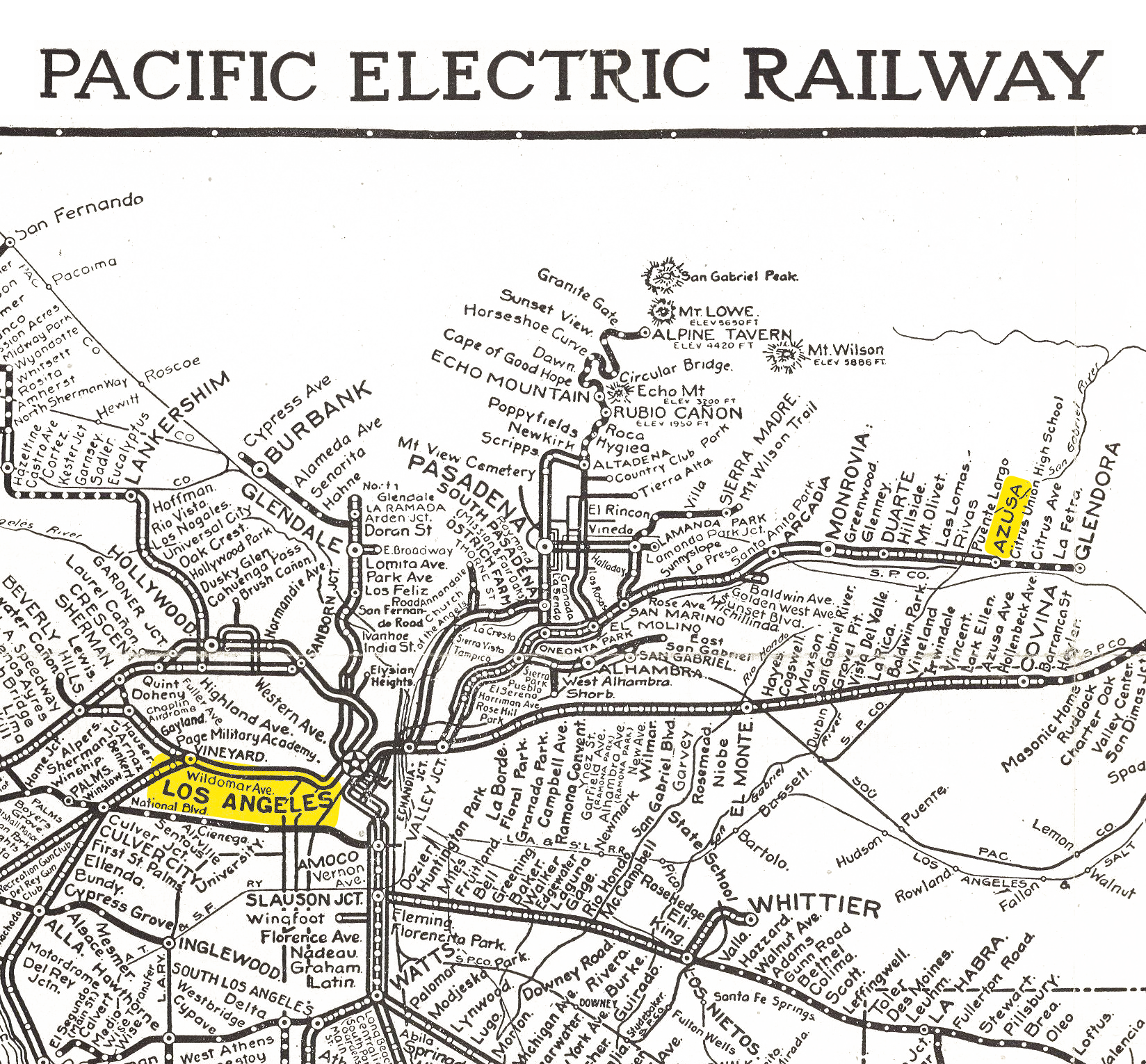

In addition it had the largest interurban electric rail system in the world. The Pacific Electric Railway’s (PE) 1,000+ miles of track connected Los Angeles to other communities across four counties.

Because Los Angeles had grown up with mechanized transportation, it never developed the density of east coast cities. Rather than growing upwords with skyscrapers, Los Angeles spread outwards, building an “unparalleled number” of single family homes. This sprawl and low density was touted as a positive feature of living in Los Angeles: “ … people moving to California ‘prefer to live away from the noise and turmoil of the city, and that the Fve and six room house takes precedent over the Gat or the apartment.”

Because of this sprawl, LA residents were highly dependent on the streetcar for transportation. In 1911, residents averaged twice as many streetcar rides as residents of other large US cities.

Streetcar movement was also often slow, and cars would get congested along LA’s narrow roads, particularly during rush hours. Because both local streetcars and interurban trains shared the same tracks, streetcar movement was often blocked, and there would be “long lines of streetcars backed up on downtown streets.“

Many problems with the electric railways ultimately stemmed from the owners’ use of them for real estate speculation. Instead of building “efficient, rational transportation systems,“ traction companies would often buy large tracts of land on the outskirts of the city, and then build rail lines to connect them to the central business district, making the land more valuable. The resulting real estate development was so lucrative that one railroad magnate, Henry Huntington, was able to “make millions of dollars in real estate investments despite the substantial losses of his interurban and streetcar empire.“

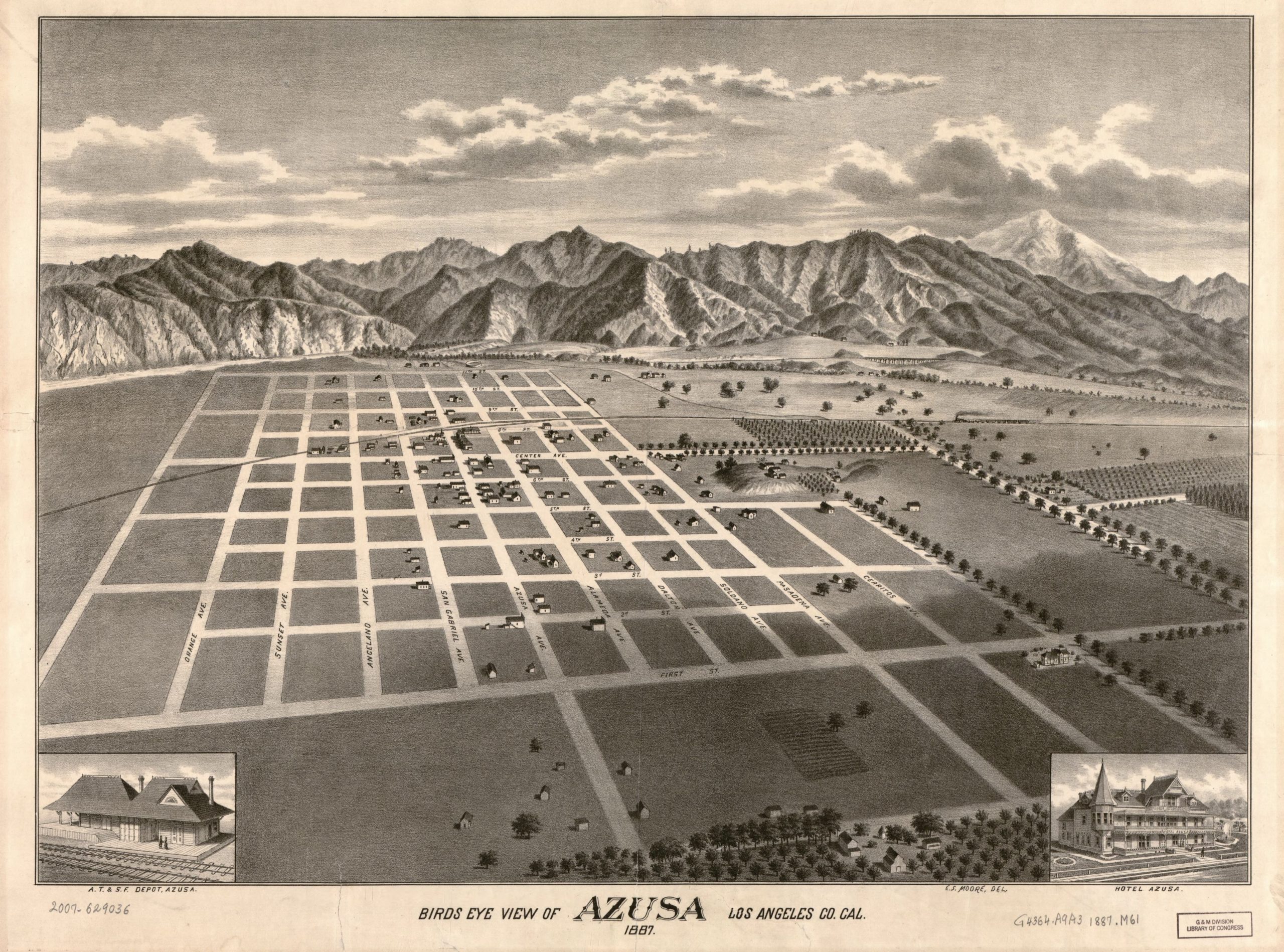

A nice example of these real estate developments is Azuza, well connected by the Southern Pacific Rail Line. Note the insert picture of the subdivision’s rail station – an important information when trying to attract customers.

Azusa lies ca. 30 miles (ca. 50 km) from LA downtown do the Northeast:

LA’s electric railways developed as a series of lines radiating from the central business district, forcing passengers to navigate through the city center to get anywhere else in the city.

“Mass transit by the second decade of the twentieth century was simply not profitable.“

Because of their poor financial performance, electric rail companies were unable to finance expansion of their systems. Between 1913 and 1925, the LA Railway Company (the city’s main streetcar operator) built only 24 miles of track, a period during which the city doubled in population. This made it nearly impossible for the electric rail companies to improve their service.

The turn to the automobile

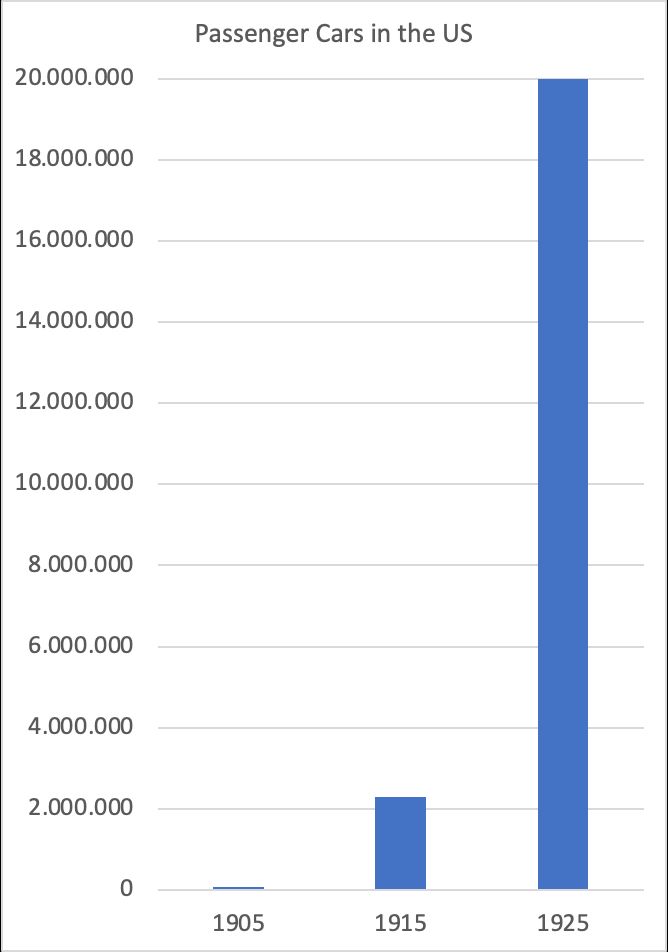

As the electric rail companies were struggling, another mode of transportation was becoming more and more attractive: the car. In 1905, there were just 77,000 passenger cars in the US. Ten years later, in part due to the enormous success of the Model T, that had risen to 2.3 million.

As cars got cheaper and higher-quality (the cost of a Model T fell from $950 in 1910 to $290 in 1925), and as Americans got richer (between 1913 and 1928 US GDP per capita increased 24%), car adoption exploded. By 1925 the number of cars in the US had risen to nearly 20 million.

Los Angeles was especially quick to adopt the car. By 1920 Los Angeles had the highest per-capita rate of car ownership in the US, four times more automobiles per capita than the US average, and eight times more than the much-denser Chicago. In 1920, 9 times as many people entered downtown LA via streetcar as via automobile. By 1924, that had nearly equaled.

Increasing adoption of cars was made possible by state and nationwide efforts to improve the quality of roads.

This happended in two stages:

- From warly 1920s, the widening, opening, and extending the existing Highways and Urban Streets

- From late 1930s, the establishment of a complete new network of Parkways and Freeways (note for the european reader: the term Highway is in the US unsed for trunk routes in the urban context while the term Free- or Parkway is used for grade-separated Motorways)

The turn to the automobile – Phase 1 – From early 1920s

The 1921 Major Traffic Street Plan recommended 200 separate projects for “widening, opening, and extending of several hundred miles of streets in the city and the county.“

„Over the course of several months in 1931, workers cleared a wide swath through three dense downtown blocks, demolishing buildings, tearing up foundations, and filling in basements—all to extend an automobile thoroughfare, Wilshire Boulevard, from Figueroa Street to Westlake.“ (Water and Power Associates)

The plan was projected to cost $25 to $50 million ($450 to $900 million in 2023 dollars), and it received overwhelming support from the citizens of Los Angeles. Both the Major Street Plan and a $5 million bond issue to raise money for it passed with overwhelming margins when placed on the ballot. A year and a half later, a property tax to raise additional money for the plan also passed.

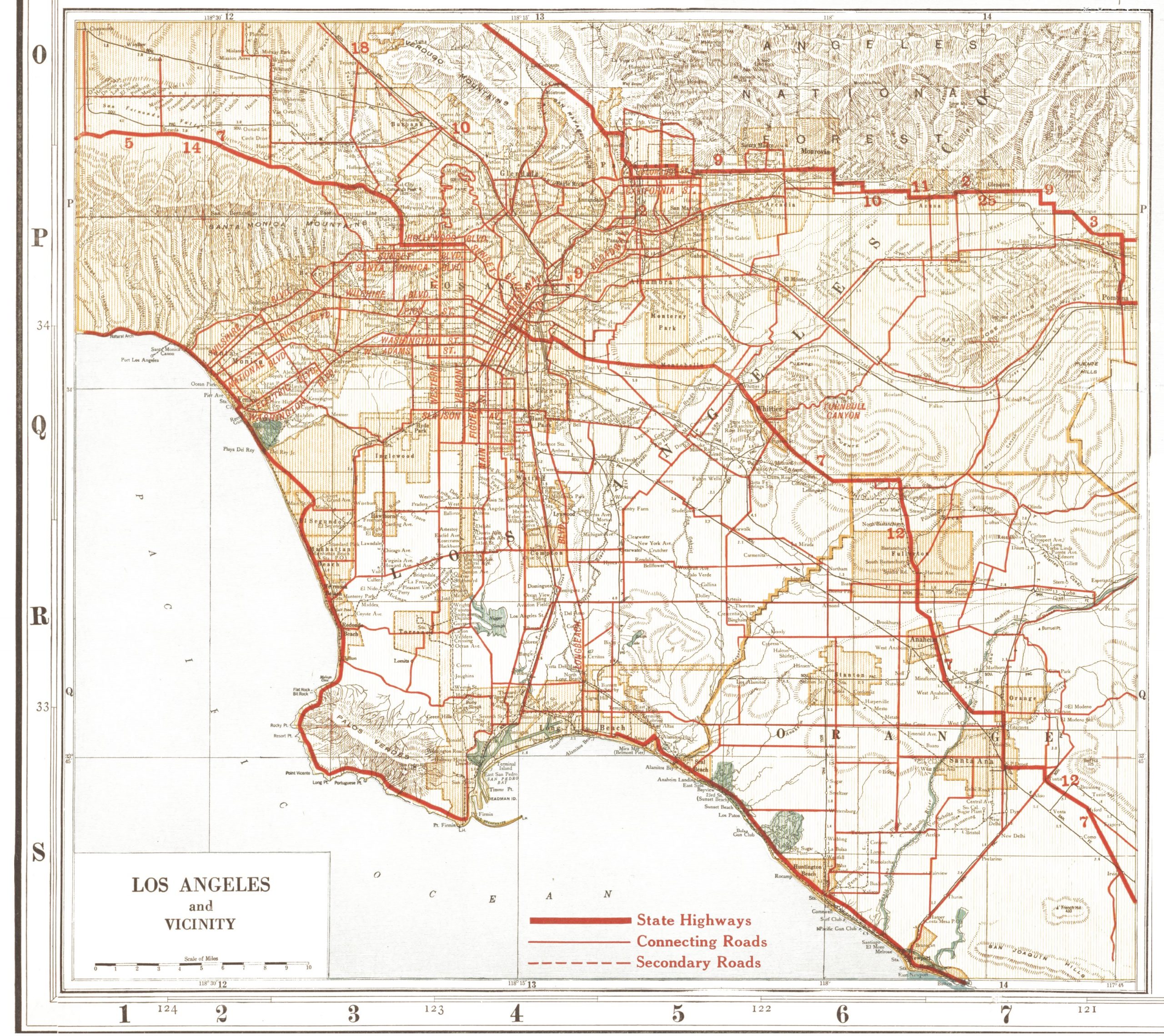

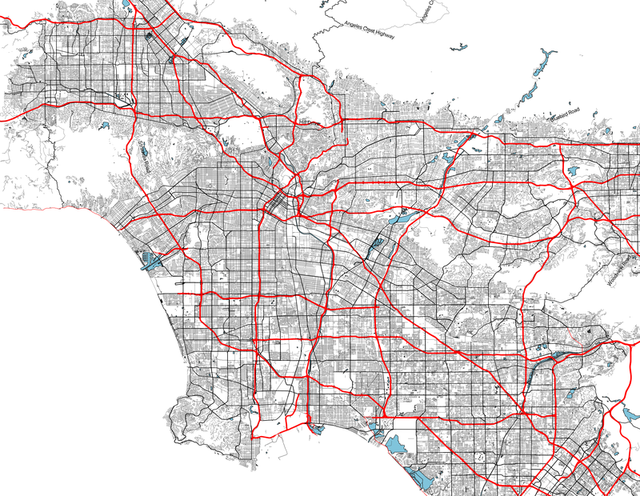

At that time the road and highway network of Los Angeles County was already well developed:

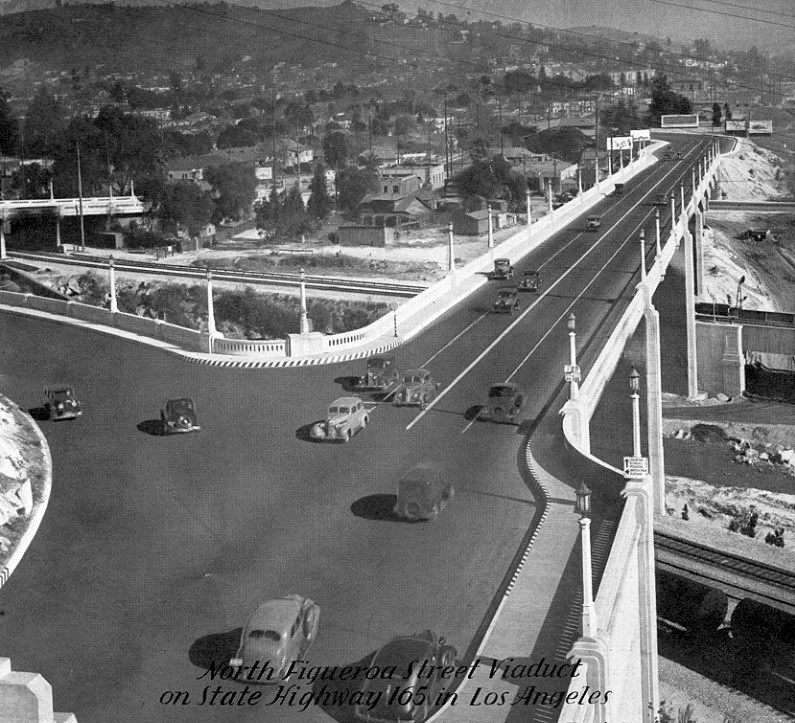

Here we see North Figueroa Street Viaduct, which was very likely also built under this programme – providing a wider and direct Los Angeles River crossing:

Los Angeles would continue to spread out. By 1940, it had one fourth to one seventh the population density as cities such as New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. Over 50% of its residents lived in single family homes, compared to just 15.9% in Chicago.

The shift in city traffic and settlement patterns continued but the metropolis started to extend to areas not connected to the rail system as did suburban development in the earlier periods for which Azusa was our example.

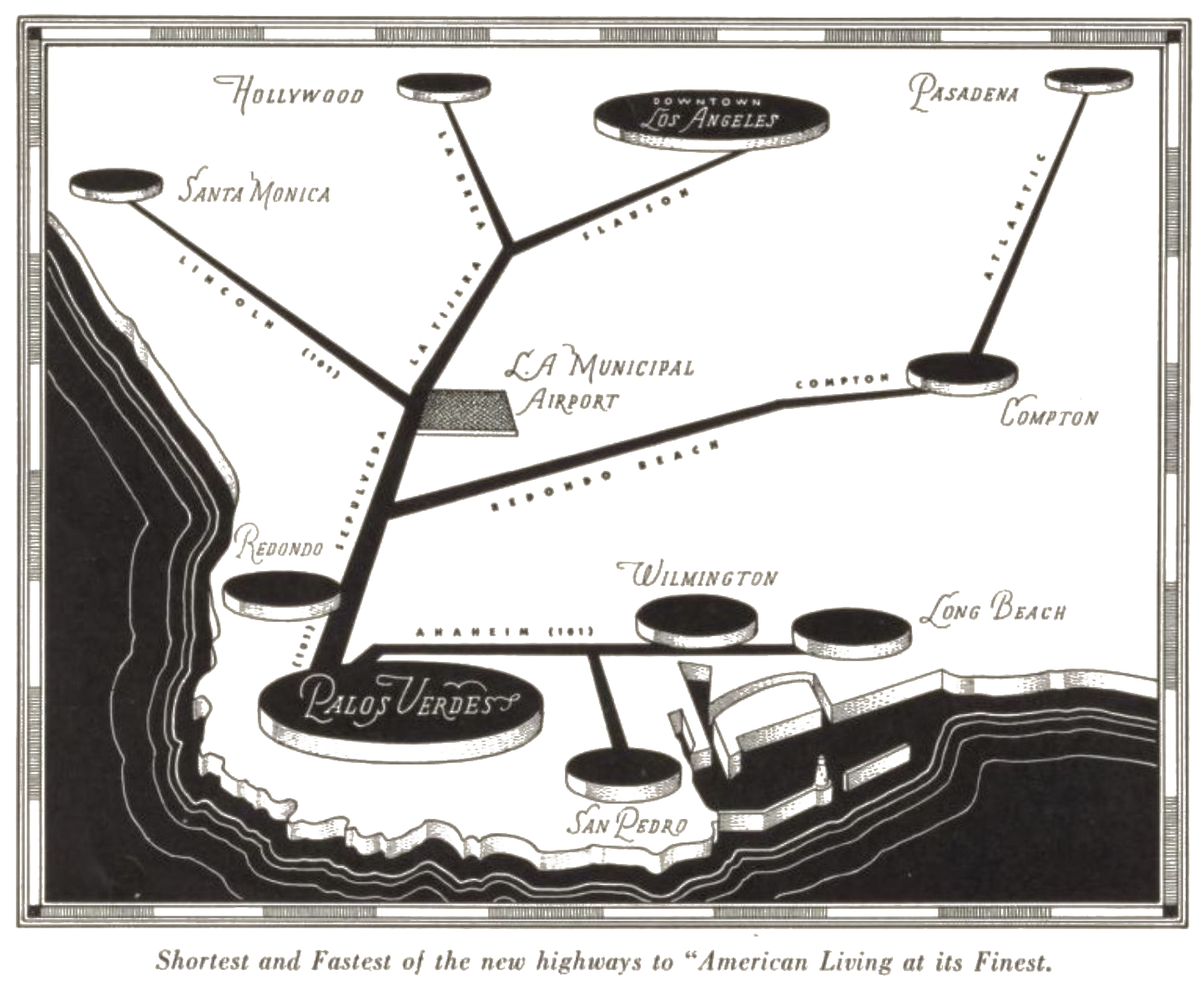

Now with the improved and extende Highway System new attractive regions in greater Los Angeles could be opened up for development; a good example being Palos Verdes, a peninsula located in the South Bay region. bordering the city of Torrance to its north, the Pacific Ocean is on the west and south, and the Port of Los Angeles is to the east:

The promotional pamphlet of 1936 makes the point very clear:

| „Palos Verdes has always been considered the most desirable residential suburb for the beach cities. During the last few years. however. several newly constructed highways have moved it considerably closer to Los Angeles. Today, Palos Verdes is only thirty-five minutes from the Wilshire Shopping District, forty minutes from Beverly Hills and Hollywood, and forty minutes from downtown Los Angeles. In other words, these new highways have made it a suburb of Los Angeles; as convenient. for example, as Beverly Hills or most of Pasadena.“ |

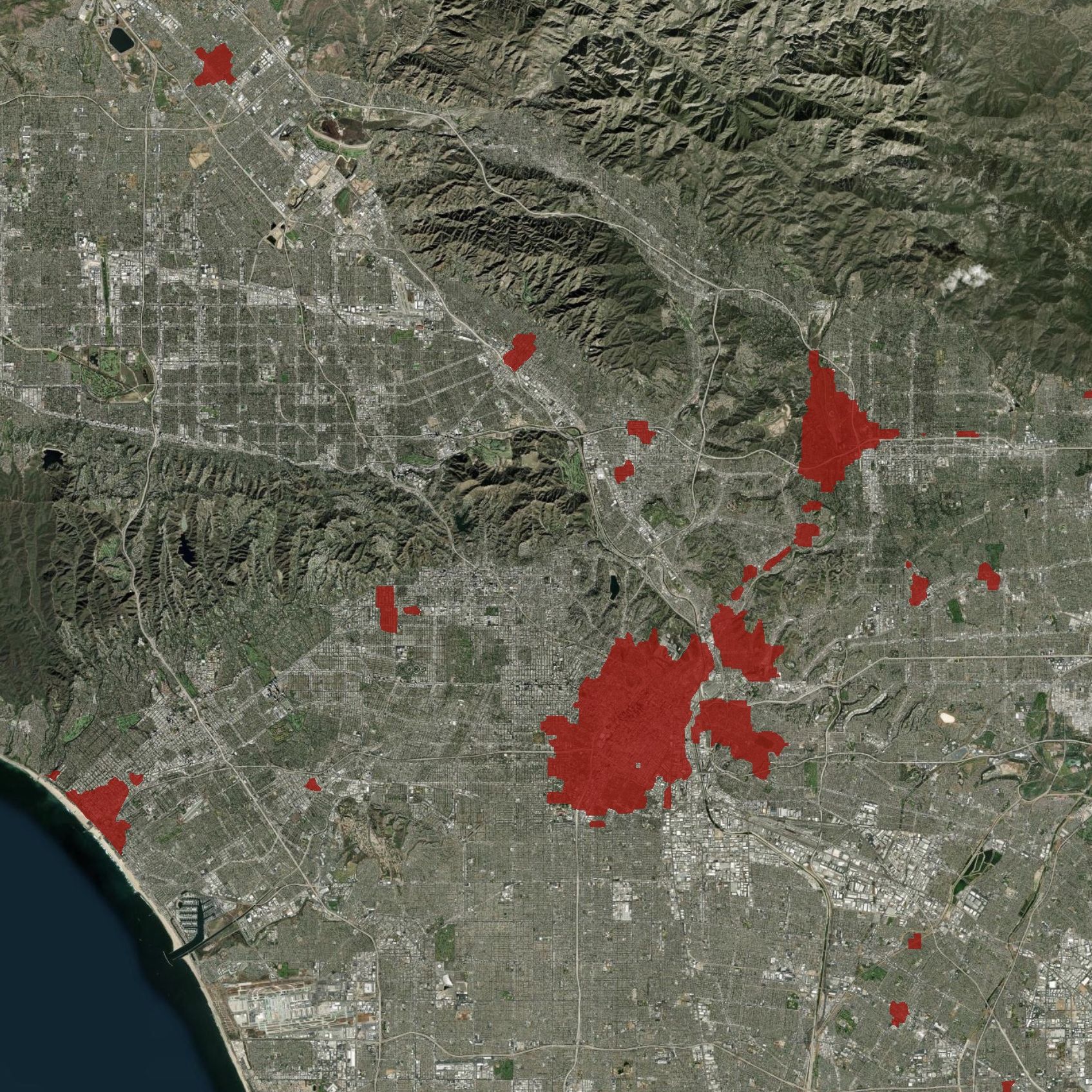

The Oil Rush

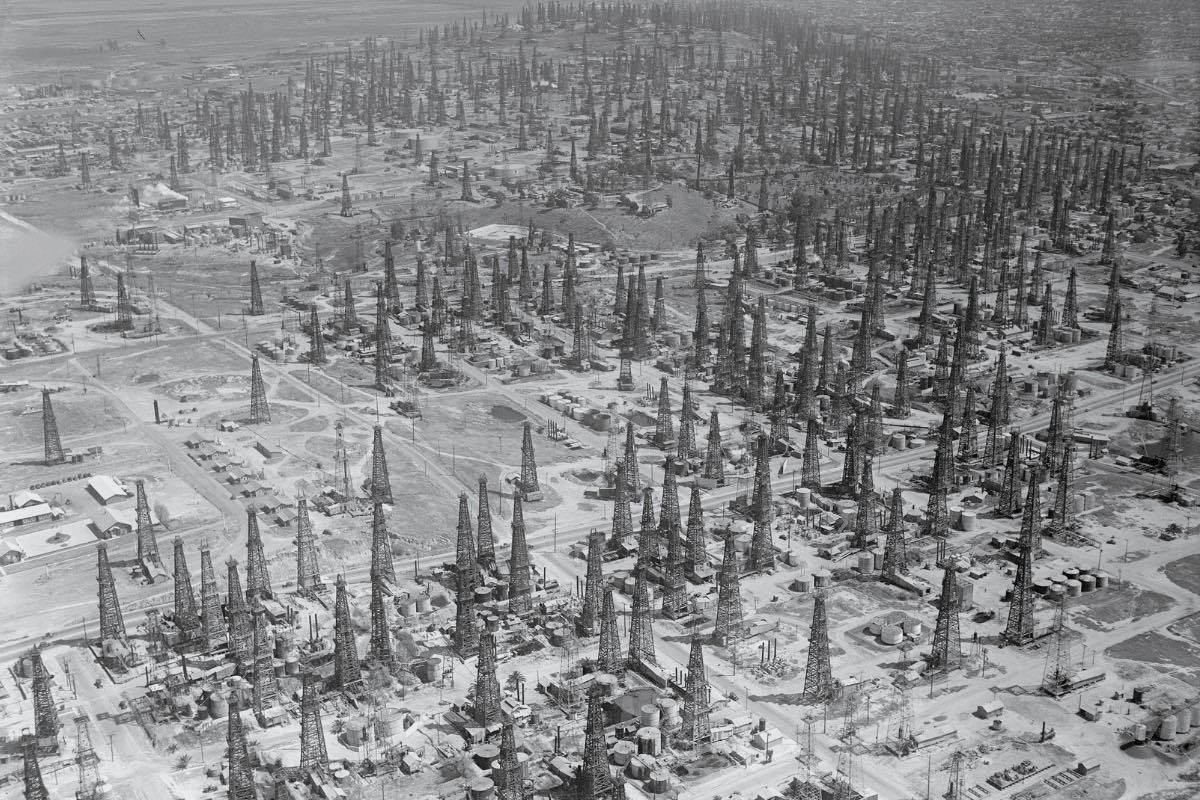

At this point we must consider another development that certainly had a strong influence on the urban turn in the 1920s and 30s: the discovery of oil in Southern California.

For the european observer it is astonishing to see how the oil industry invaded the urban landscape of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area:

One can imagine that when oil springs up your frontyard you would tend to use an automobile rather than the suburban train.

By 1923, the LA region was producing one-quarter of the world’s total supply. Even today it is still a significant producer, with the Wilmington Oil Field having the fourth-largest reserves of any field in California.

The struggle of mass transit

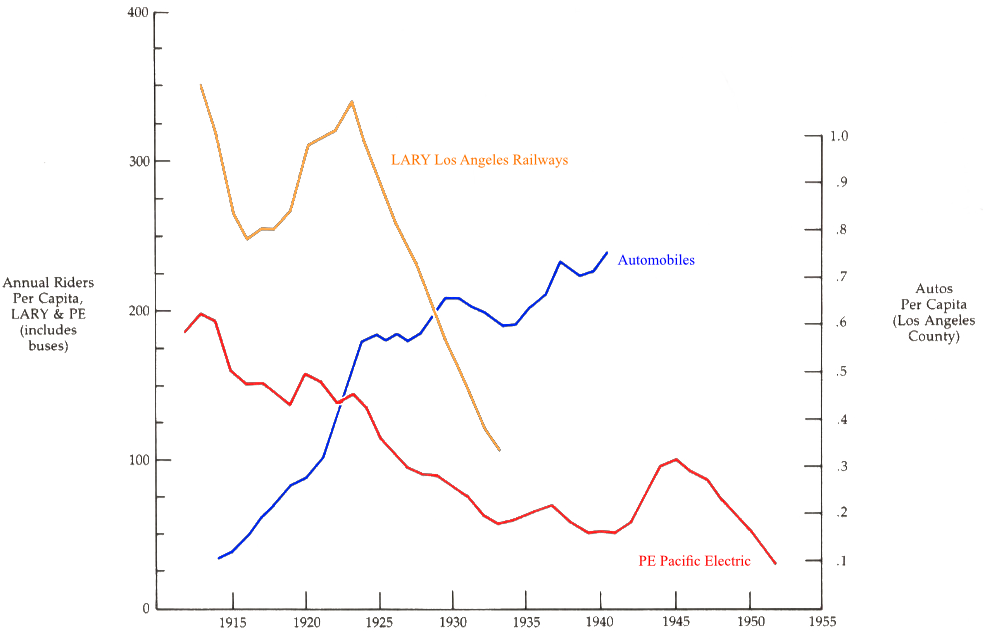

As LA’s streets improved, people increasingly opted to travel by car rather than by streetcars or interurban trains. By 1930, ridership on both the local LARY and the interurban PE had fallen to less than half their peaks.

Nevertheless, streetcars and interurbans continued to carry millions of people in LA, and it was widely assumed that they would continue to play a critical role in LA’s transportation infrastructure. Following the success of their Major Street plan, the Traffic Commission and the city council commissioned another consultant report for improving the city’s mass transit infrastructure. The report found that Los Angeles was a challenging city for mass transit: unlike other cities, LA’s population was widely dispersed in single family homes, and the resulting low density made a mass transit system challenging:

„…rapid-transit lines could not operate self-sufficiently in the absence of high population densities. Even cities such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia found it necessary to subsidize their systems.“

The consultant’s report ultimately recommended segregating di[erent kinds of transit, removing streetcars from roads and replacing them with elevated trains or subways. But while there had been widespread agreement about the necessity of improving LA’s streets, there was no such agreement on how to implement mass transit improvements.

Subways were extremely expensive to build. Critics noted that “New York City … had spent about $1 billion on its underground system. Yet it continually lost money and required substantial public subsidies to operate.“ Because of the traction companies’ financial struggles, it was impossible for them to finance the construction of an underground system themselves, and residents widely opposed either subsidizing their operations or being forced to pay for the improvements themselves.

As technology was making a decentralized, spread-out city more feasible, many felt that such a city would be more desirable. The Los Angeles City Club argued that “Los Angeles should reject the centralized city structure of eastern cities in favor of a ‘harmoniously developed community of local centers and garden cities’.“

Disagreement over the form it would take and who would pay for it assured that “the city would not build a rapid-transit system during the next forty years.“

Without being able to improve their systems, the traction companies continued to struggle, and by 1938 80% of transportation in LA was provided by private cars.

The turn to the automobile – Phase 2

Introduction of the freeway system from late 1930s

Thanks to the car, as well as “white flight” to the suburbs, LA would continue to spread out. By 1940, Los Angeles had one fourth to one seventh the population density as cities such as New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. Over 50% of its residents lived in single family homes, compared to just 15.9% in Chicago.

This ultimately resulted in a shift in city traffic and settlement patterns.

Because LA grew so late, and adopted the car so early, this decentralization and urban sprawl appeared there first. But ultimately most other US cities followed a similar path of decentralization. In the 1920s, 60% of new homes in the US were single family homes, and between 1938 and the beginning of WWII, this rose to 81%.

Initially, urban planners embraced the decentralization brought on by the car:

„The automobile, they believed, could once and for all change the spatial organization of the metropolis. No longer would urban dwellers have to suffer from the crowded and unhealthful conditions of the walking city. Streetcars had given Americans a glimpse of the suburban ideal. Now it appeared that the automobile could fulfill the promise of residential dispersion.“

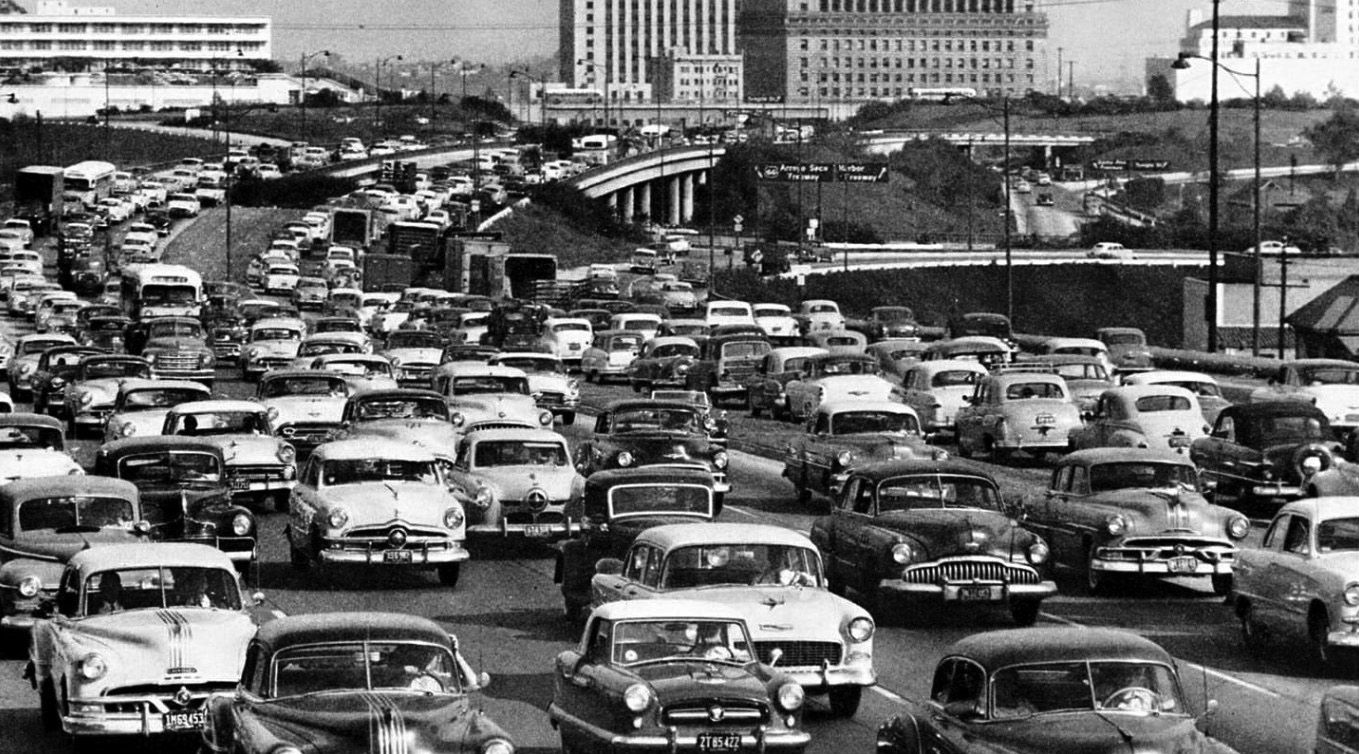

However, by the 1930s, city planners had realized that “something had gone wrong.“ Traffic congestion continued to be a problem, both in the city center and, increasingly, in suburban areas outside the city center. Land values in the central business district declined, and housing conditions deteriorated as middle-class residents left for the suburbs.

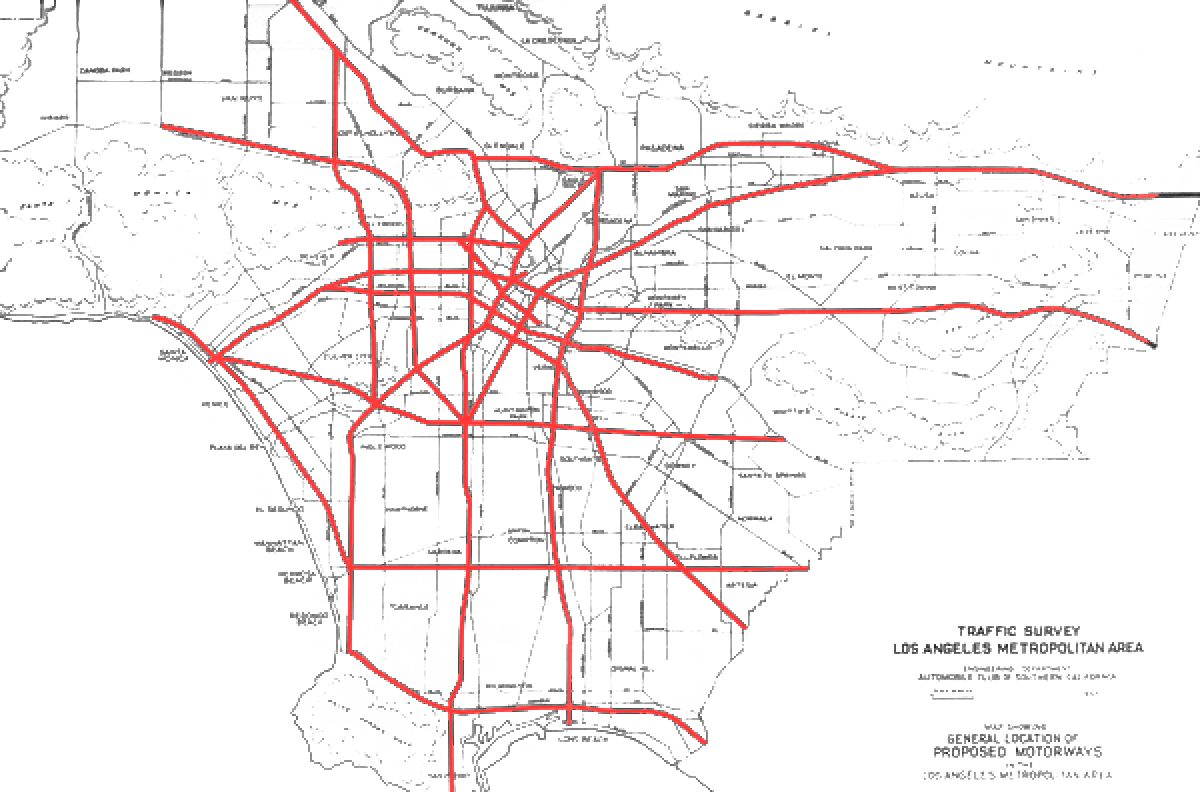

In response, planners proposed another road expansion program. But rather than enlarging existing city streets, this time they proposed a system of expressways, roads where traffic would flow continuously, unencumbered by intersections, stoplights, or cars entering and leaving at any point.

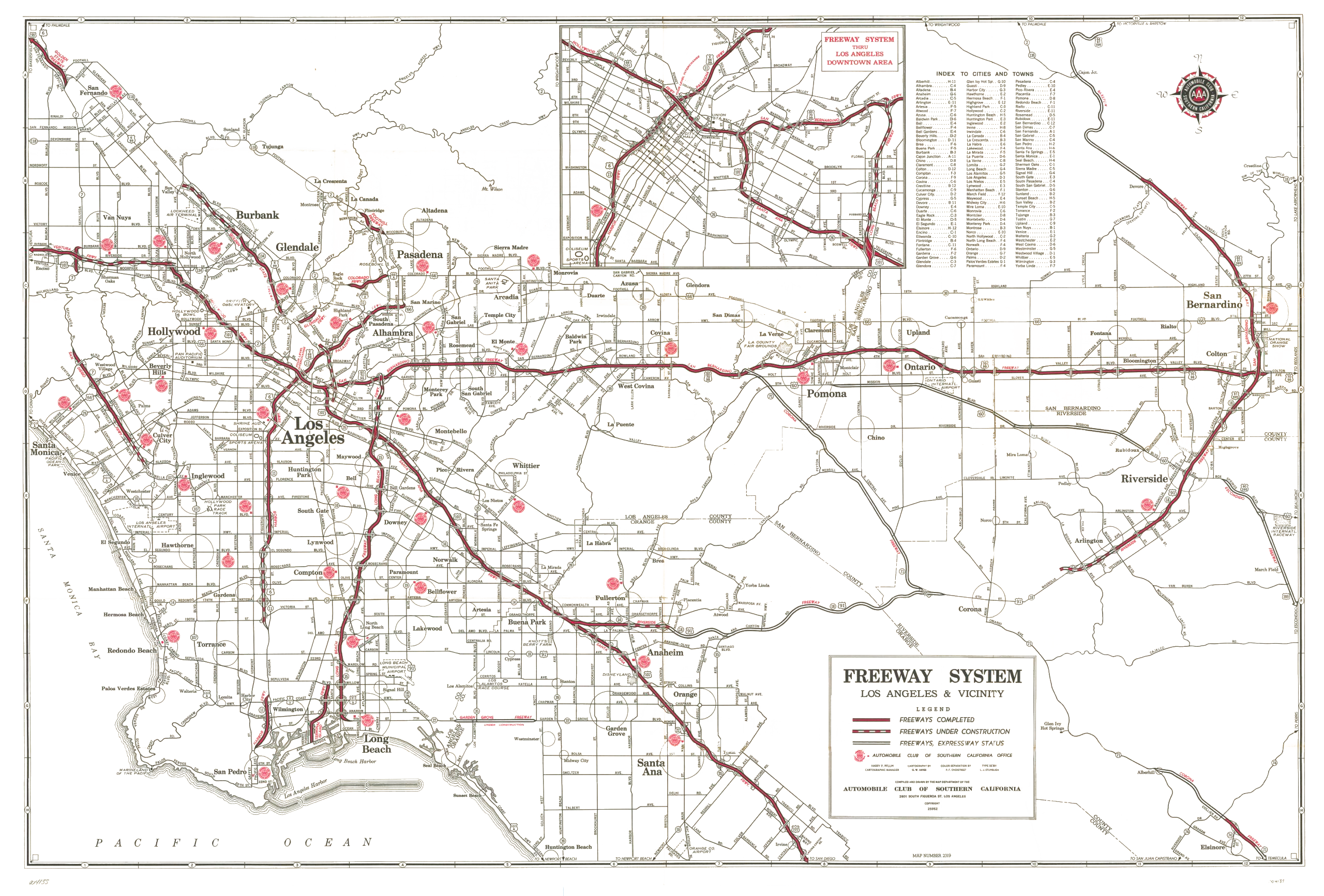

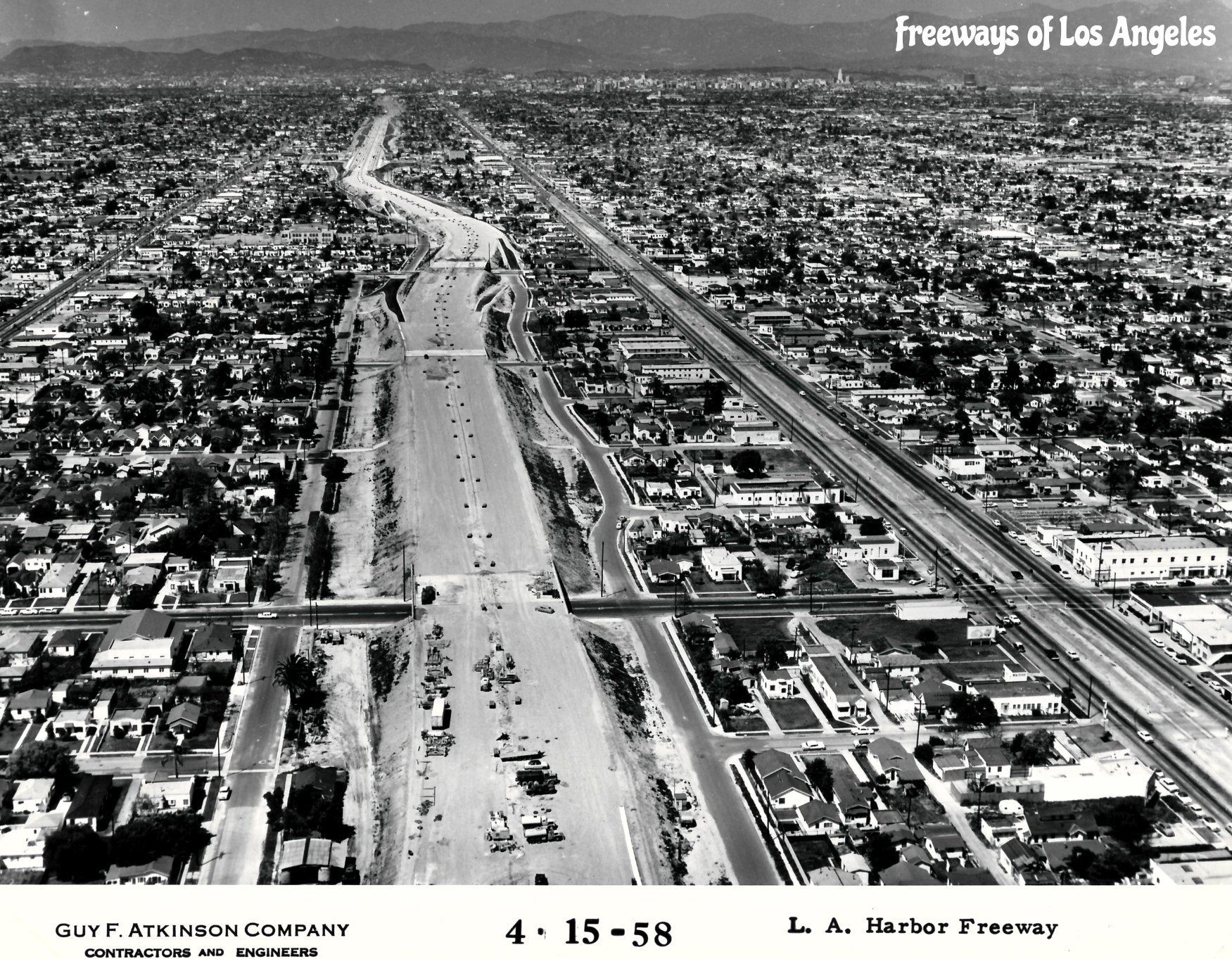

Realizing such a large system within the existing urban fabric did take some time: Construction of southern California’s expressway system was interrupted by WWII, but resumed after the war, and by 1958 southern California had completed 20% of its original plan.

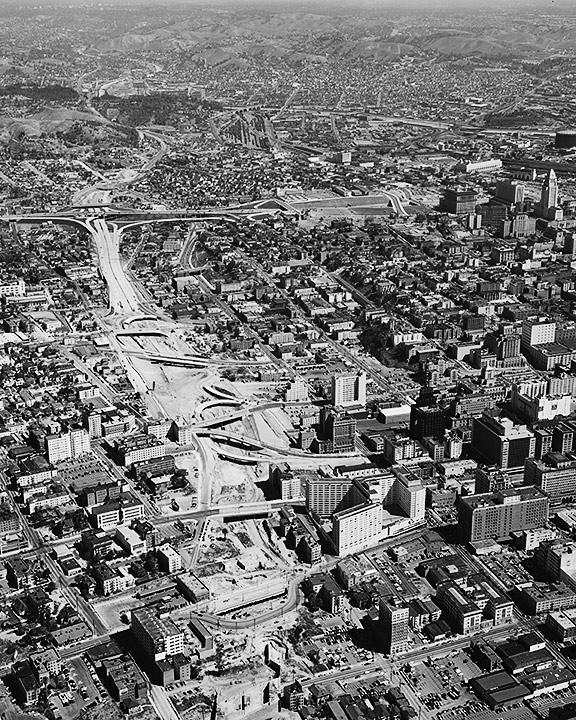

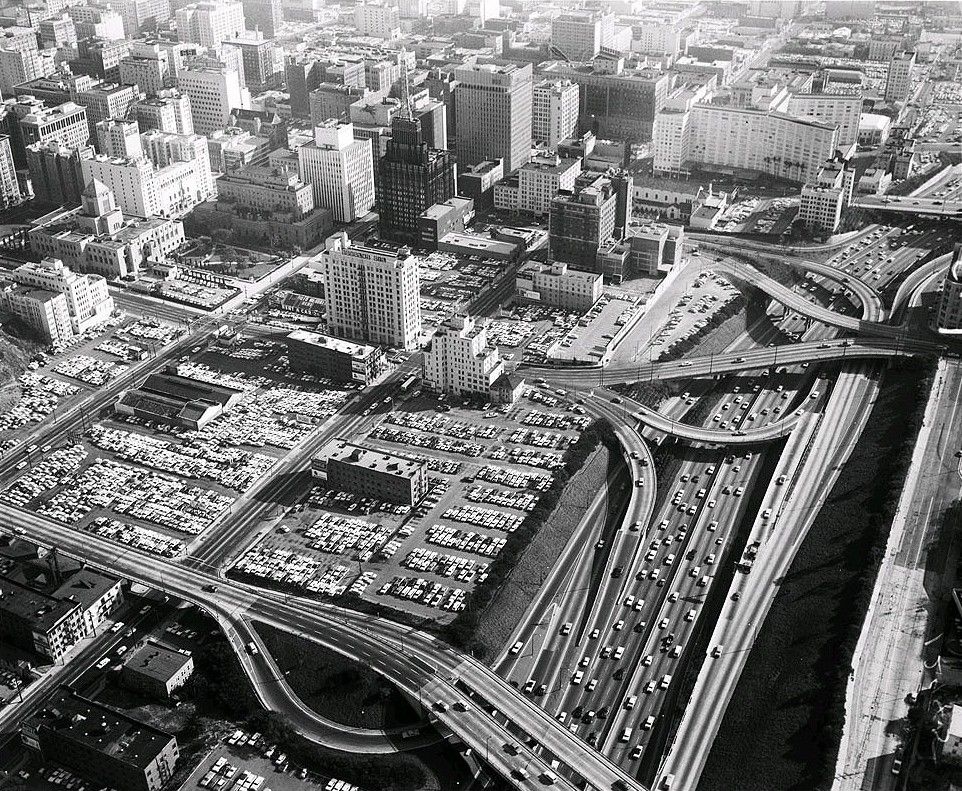

These Fotos show that constructing the freeways meant a brutal intervention in established urban districts. This aspect is described in more detail on this page.

What we see when looking west at newly constructed Ventura Freeway (see foto below) was the dream of Motorway planners and motorists alike: free travel on free roads.

Urban Sprawl – Phase II

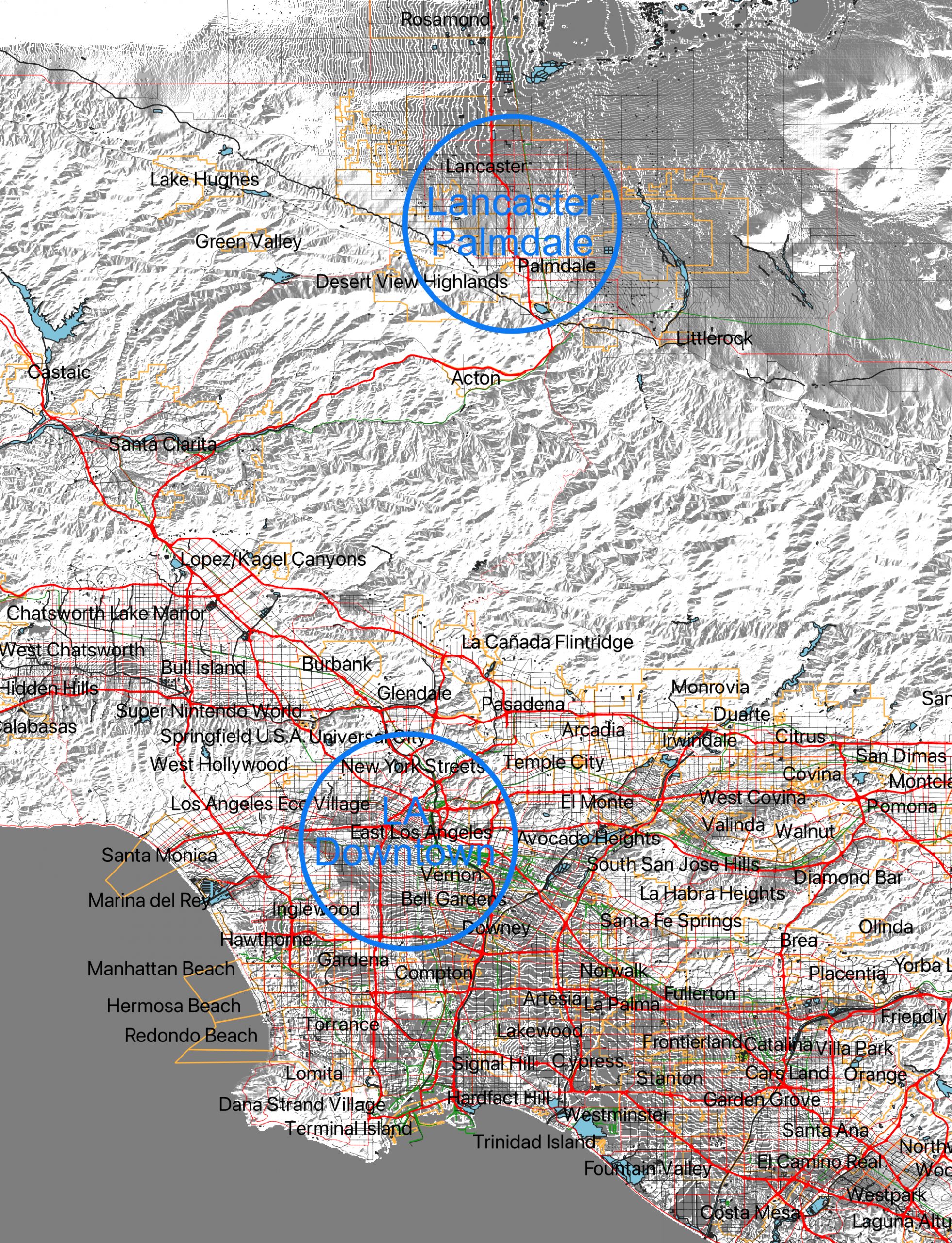

With the Freeway (Motorway) System the shift in city traffic and settlement patterns continued even further: the metropolis spreads to far away areas like e.g. Palmdale / Lancaster – 70 Miles (112 km) north of downtown LA, North of San Gabriel Mountains.

The two cities grew from 25.000 in the early 1960s to a population of over half a Million in line with the extension of State Motorway No 14 towards the Mojave Desert.

Congestion – Phase II

But as with street expansion, the implementation of Motorways ultimately didn’t solve the problems of congestion. By the 1960s, they “were jammed with cars at rush hour as Angelenos had become almost totally dependent on their automobiles for transportation.“

Parking

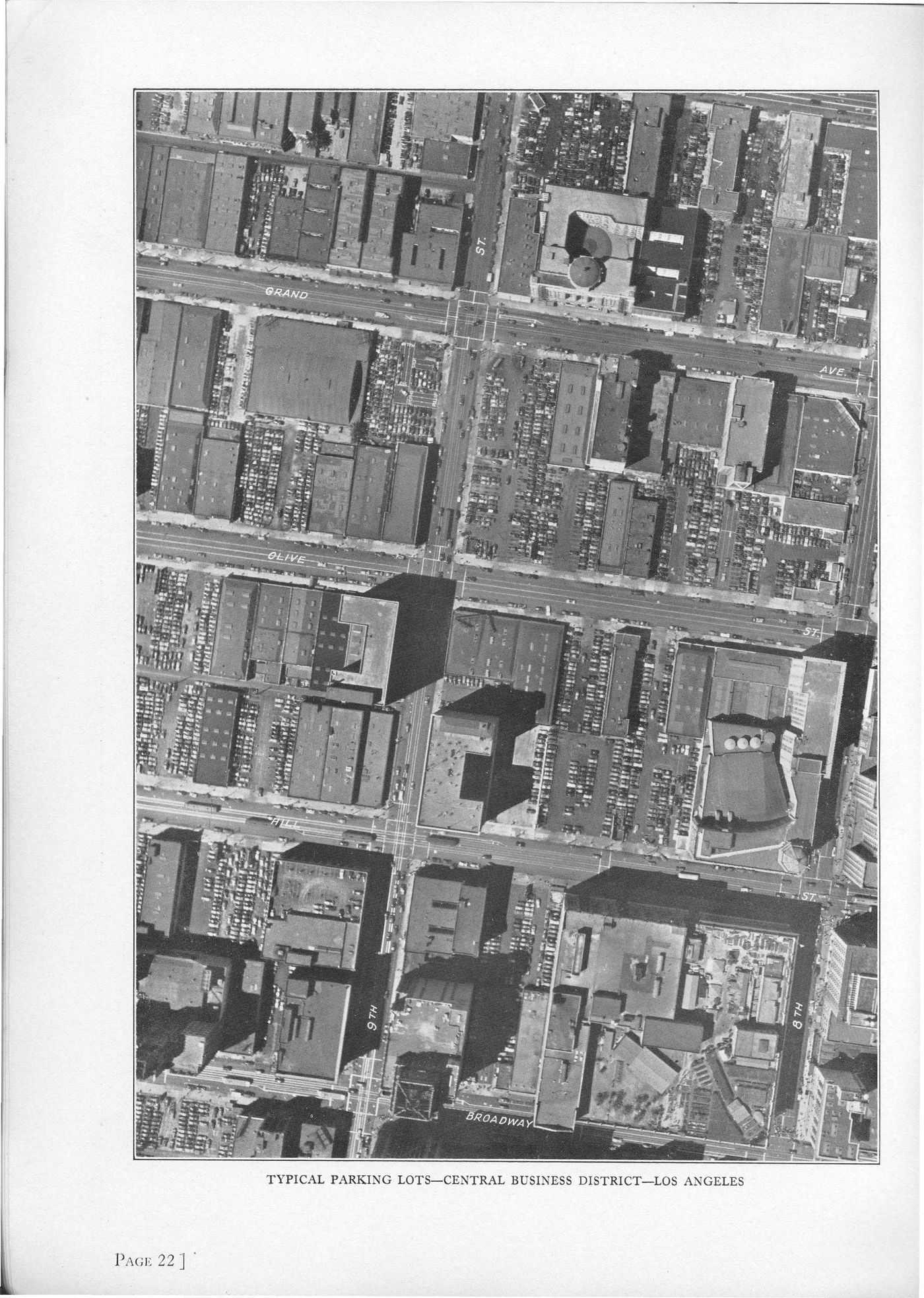

The following foto shows very strikingly how the car-oriented mobility structure also puts its stamp on the urban fabric in the very city core: cars are dominating the city even when not moving. In German we have a nice term for this: Stadtfraß, meaning that city space is eaten up by cars like leafes by ants or beetles.

In the Traffic Survey of 1937 comissioned by the Automobil Club of Southern California parking in downtown LA was a major issue:

The study recommended „that if private initiative does not provide adequate off-street parking facilities consideration be given to the acquisition and operation of such facilities wherever needed by a public authority … [and] … a uniform parking fee be assessed against all registered motor vehicles in the Los Angeles area in an amount sufficient to cover the cost of land for parking facilities …“

Combining Freeways with Rail Transit

In the early years of Freeway rail lines for Pacific Electric were included as we can see here on Hollywood Freeway:

Pacific Electric Railway trolleys in the center of the Hollywood Freeway through Cahuenga Pass, 1952. Source: Water and Power Associates

However, a few years later – when the transit systems became more and more unprofitable – the rail lines were given up and the space used for the addition of more Freeway lines:

At the end of rail lines in the early 1950s tracks were removed from the streets all over LA and the neigboring cities like the City of Monrovia in the Northeast of the LA Metropolitan Area. Thus giving cars more space, continuing in a way the street widening program of the 1930s: