Frankfurt am Main has undergone a series of major transformations over the centuries, each marking a turning point in its urban development. Here’s an overview of the key phases and turning points, from the Middle Ages to today:

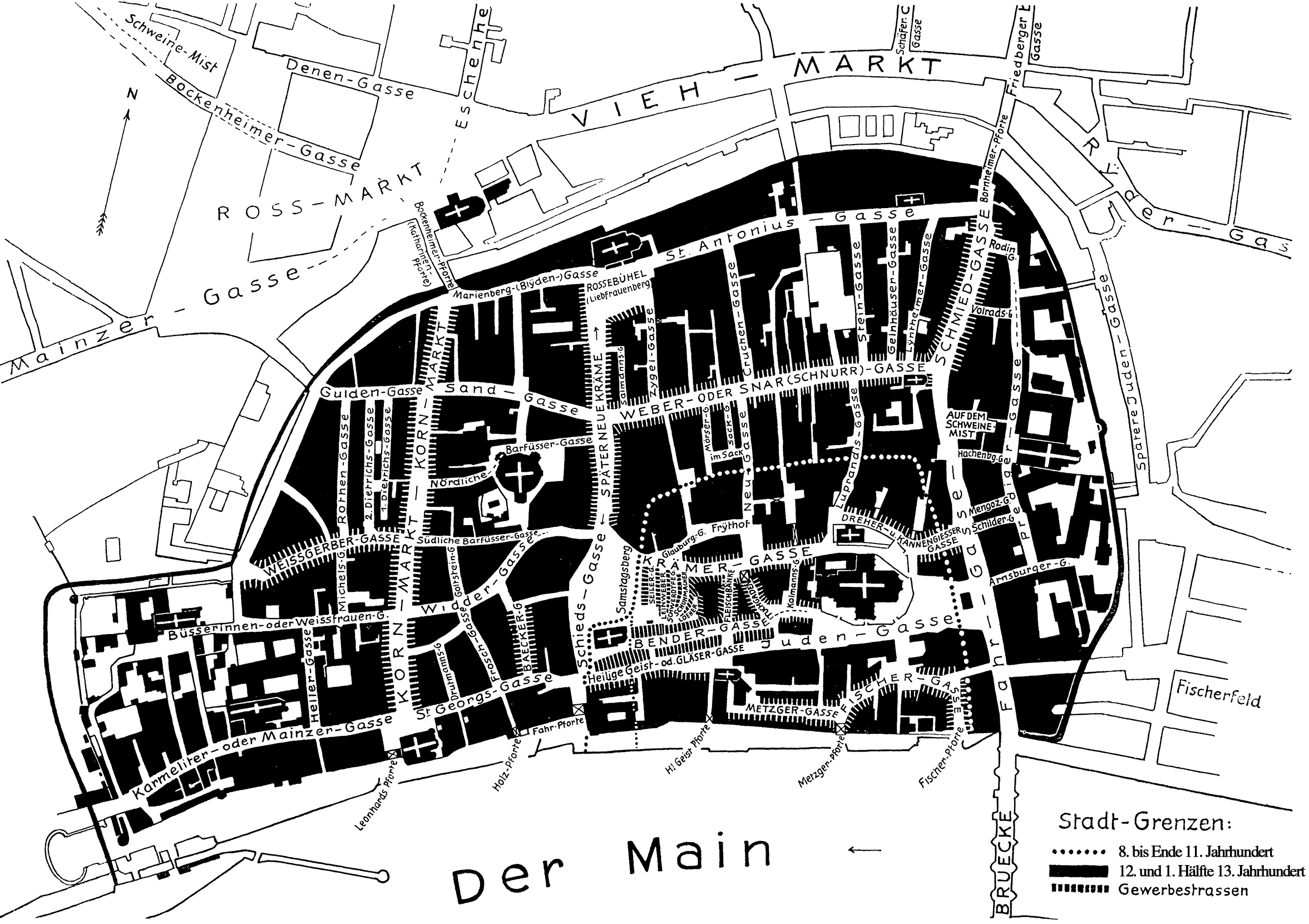

1. Medieval Foundation and Early Urban Form

(up to ~1600)

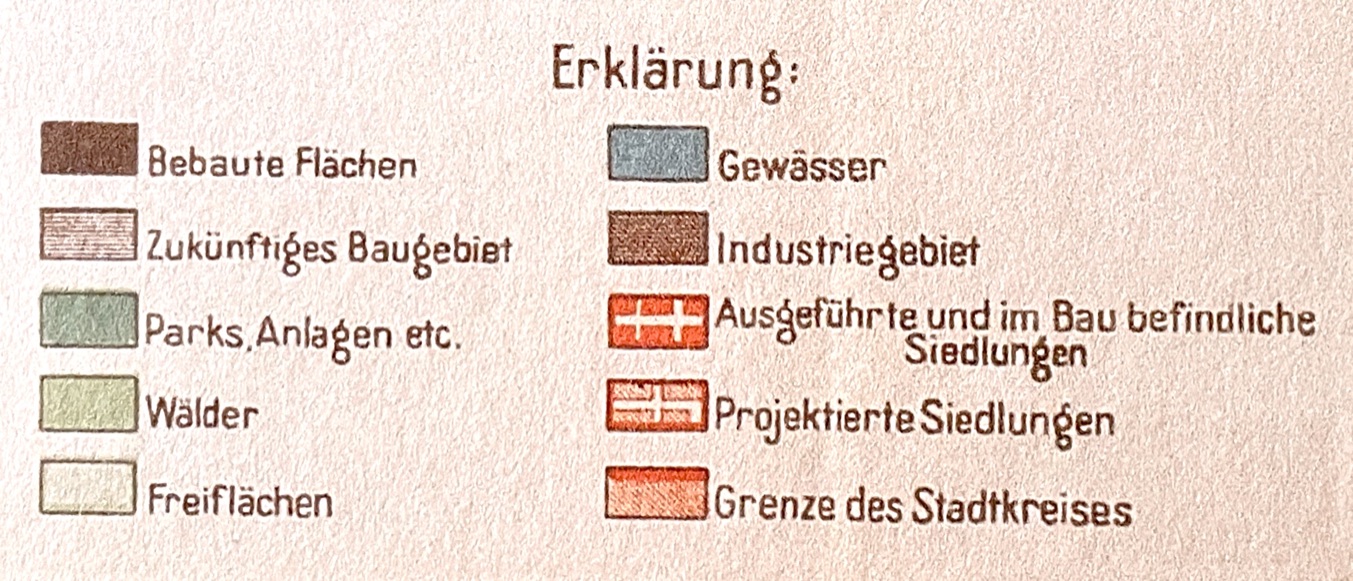

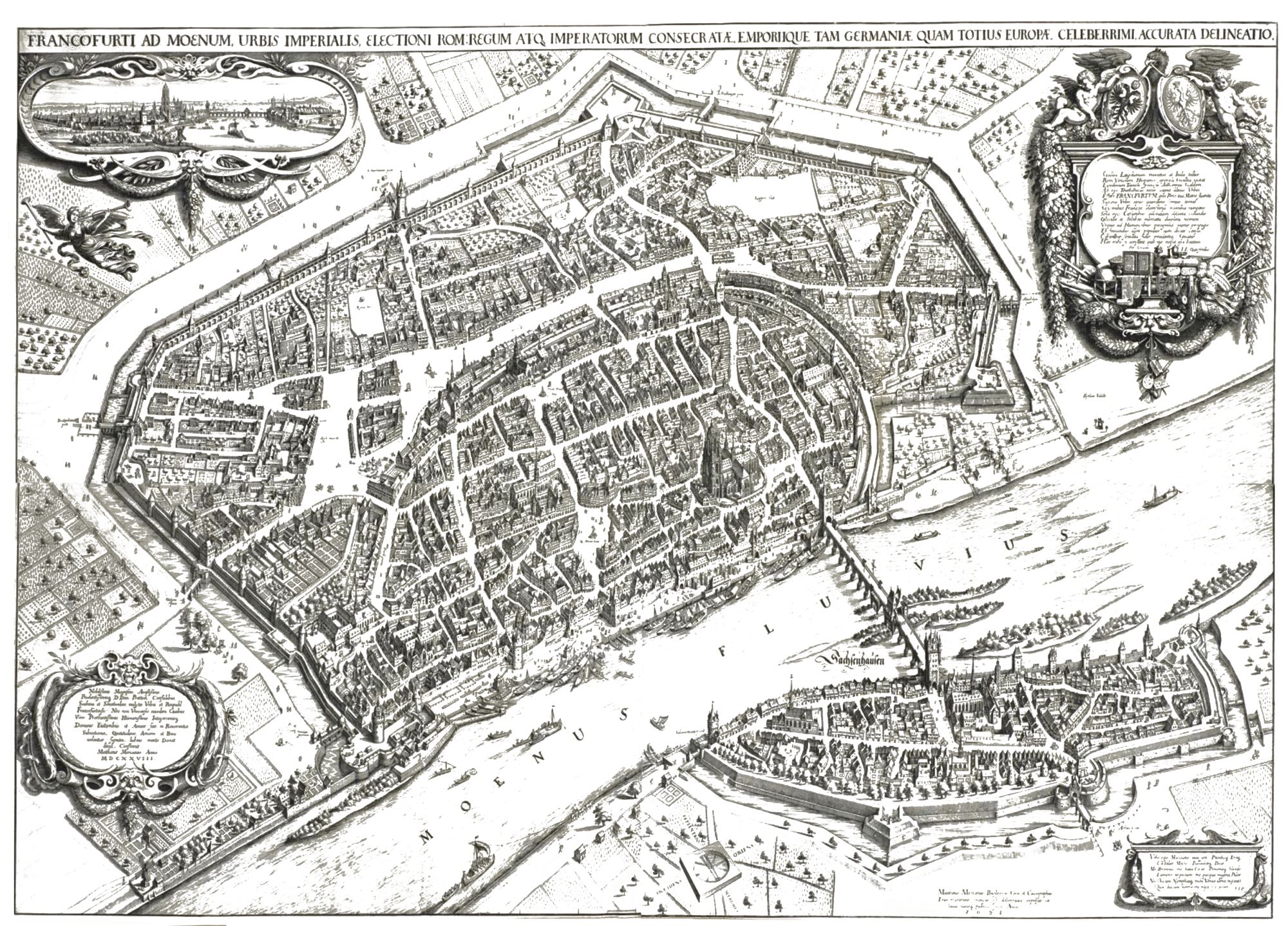

Großer Stadtplan von Südwesten, 1628, Source: Historisches Museum Frankfurt

Der große Stadtplan von Matthäus Merian d.Ä. zeigt Frankfurt aus der Vogelperspektive von Südwesten. In der Stadt lebten zu dieser Zeit etwa 20.000 Menschen. Manche von ihnen sind als Reiter oder Fußgänger zu erkennen.

- Turning point: Establishment as an imperial city and trade hub.

- Key developments:

- Around the 8th–9th centuries, Frankfurt emerged as a royal palace (Pfalz) under Charlemagne.

- Granted imperial city status in 1372, giving it autonomy within the Holy Roman Empire.

- Hosted imperial elections and coronations in the Römerberg area — shaping the medieval core.

- Developed a compact, walled city on the north bank of the Main; the medieval street network still influences the Altstadt’s layout.

2. Early Modern Expansion and Trade Prosperity

(1600–1800)

- Turning point: Rise as a trade and financial center.

- Key developments:

- Frankfurt’s Trade Fairs (Messe) gained European importance.

- Banking and money exchange activities began, laying groundwork for its later financial dominance.

- Growth remained moderate — the city stayed within its medieval walls until the 18th century.

3. Industrialization and Urban Growth

(1800 -mid-19th century)

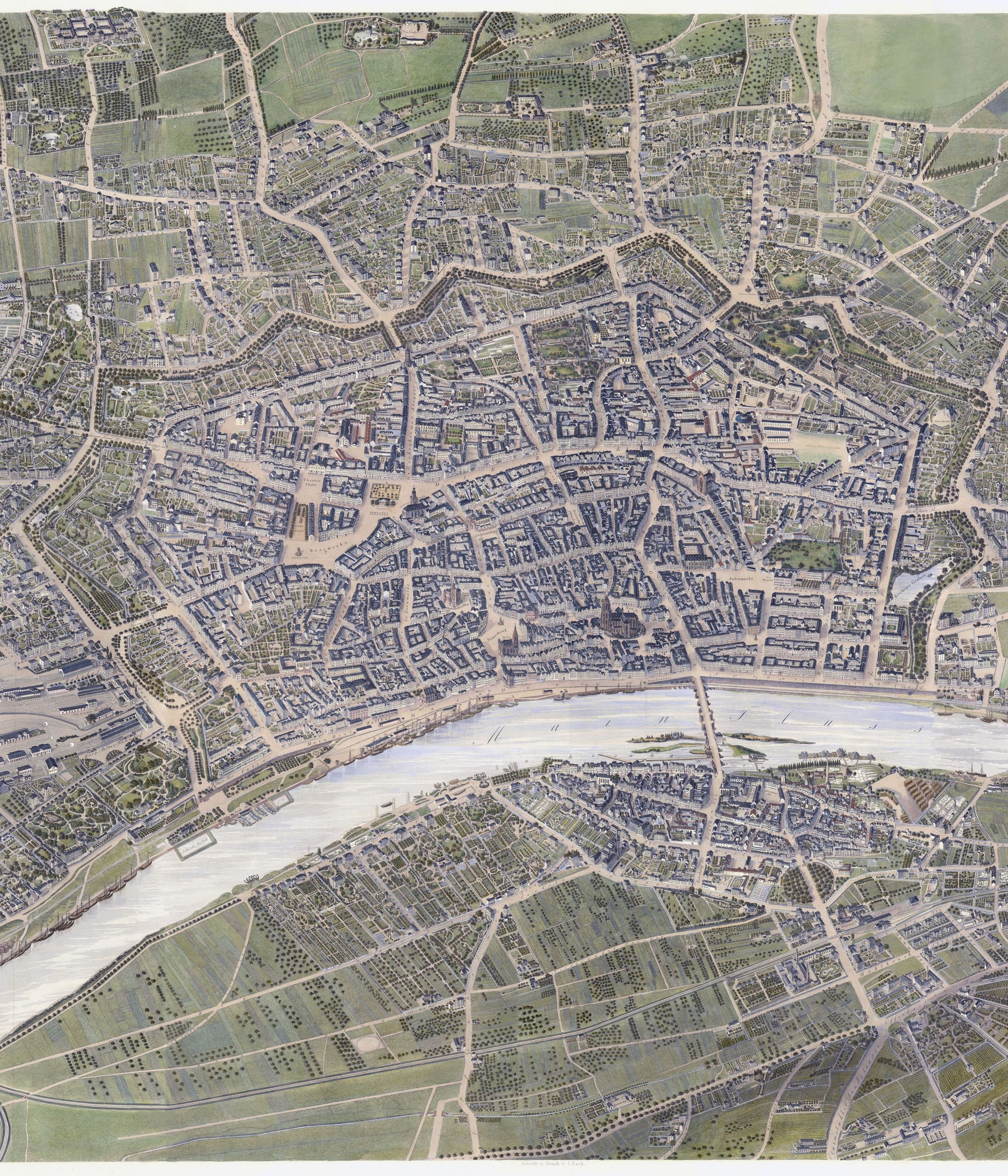

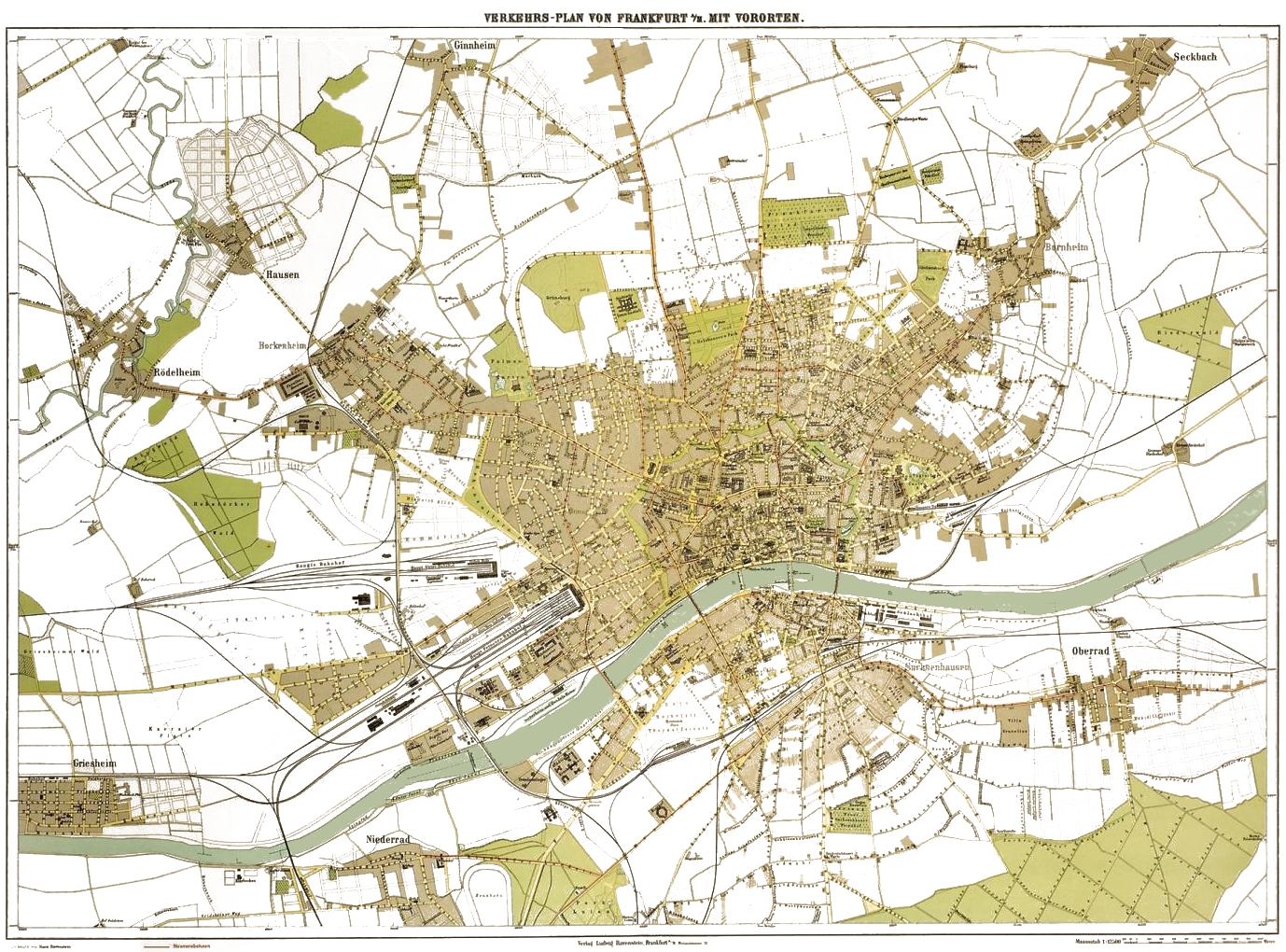

Frankfurt, Verkehrsplan 1899

Frankfurt, Verkehrsplan 1899

- Turning point: Transformation from a small trade city to an industrial metropolis.

- Key developments:

- After joining the German Customs Union (Zollverein) and later becoming part of Prussia (1866), industrialization accelerated.

- The Main-Neckar Railway (1846) and other lines made Frankfurt a transport hub.

- Fortifications demolished → creation of the Wallanlagen (green belt) around the old city.

- New neighborhoods like Bahnhofsviertel, Westend, and Nordend developed.

4. Modernist Expansion and Planning

under Ernst May (1920s)

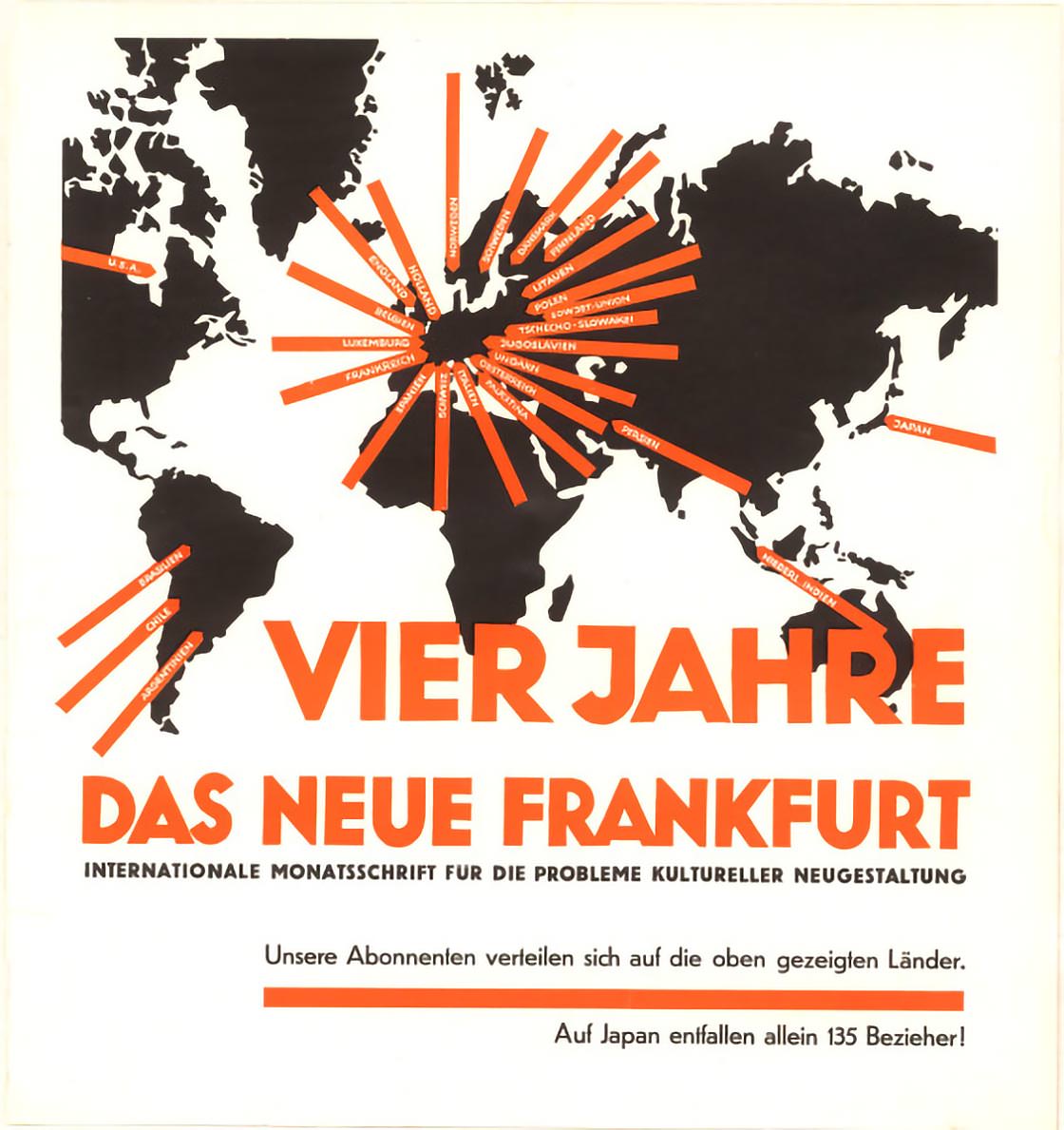

- Turning point: The „Neues Frankfurt“ (New Frankfurt) urban reform program (1925–1930).

- Key developments:

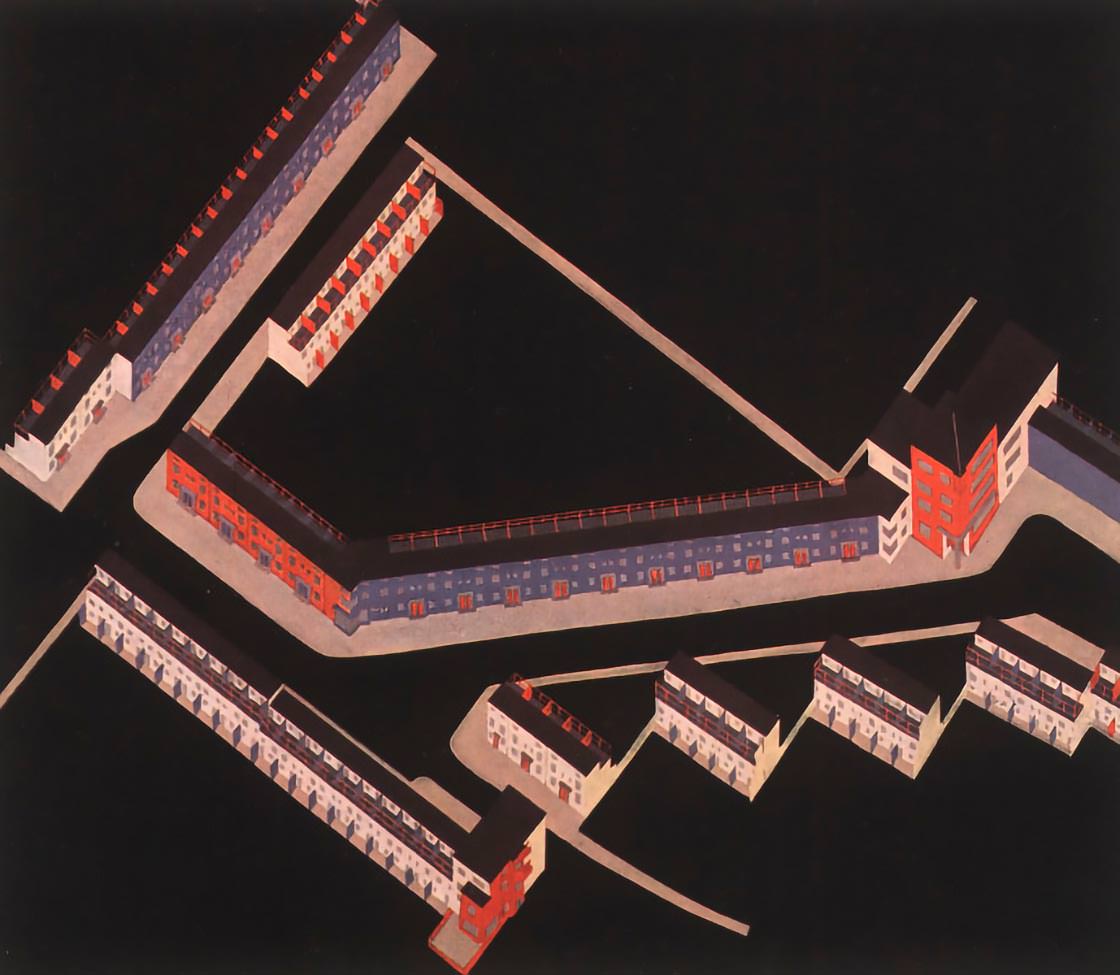

- Under city planner Ernst May, Frankfurt became a global model for modern urban housing.

- Creation of large-scale modernist housing estates (e.g., Römerstadt, Praunheim).

- Introduction of urban zoning, modern infrastructure, and public housing standards.

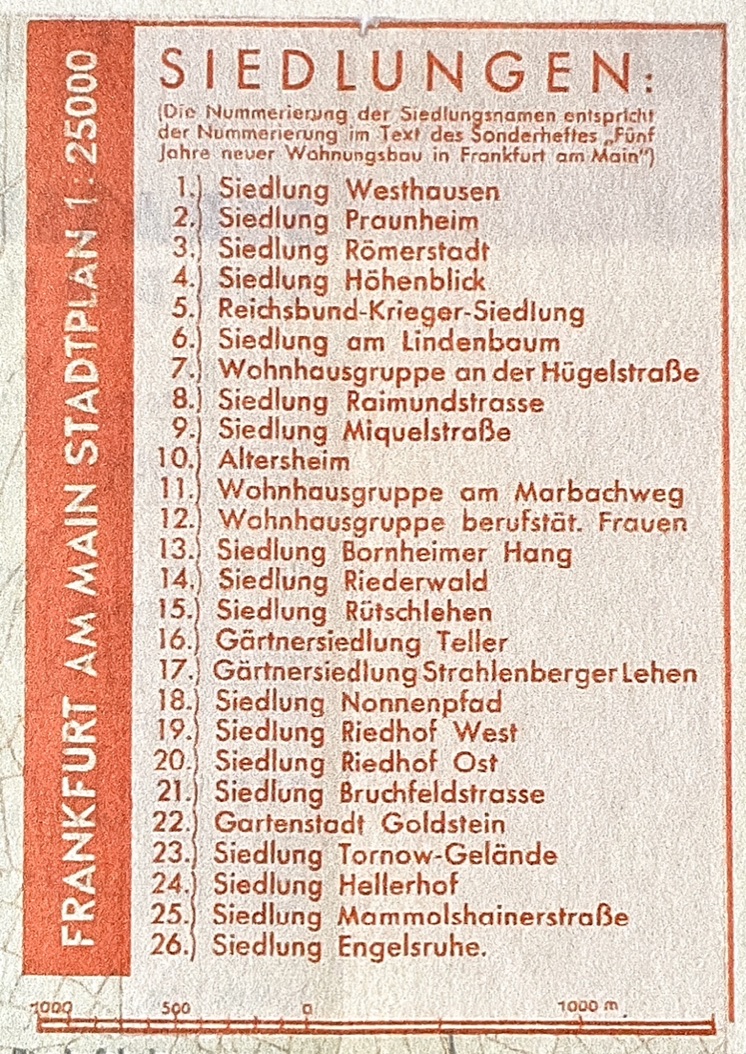

The New Frankfurt urban planning programme (1925–1930) leaves a lasting mark on the city.

„Neues Frankfurt“ was the name of an urban planning programme of the years 1925 to 1930. Through the incorporation of outlying communities, the city’s population had grown to 574,000. The monetary crisis and mass unemployment brought about a high demand for affordable living space. Public housing was therefore the chief concern.

Mayor Ludwig Landmann strongly promoted house construction activities. Ernst May, the head of the municipal buildings department, gave New Frankfurt a face. He brought architects and designers to the town who developed holistic and economical concepts for new types of housing. Not only the construction, but also the interior furnishings were to adhere to architectural conceptions of beauty and functionality.

Rationalization with the aid of standardization, grids and systems was to bring down the construction costs.

Among the largest are Bornheimer Hang, Praunheim and Römerstadt, which stretches out along the River Nidda like a fortified settlement. New districts sprang up quickly thanks to prefabricated construction methods. The „Frankfurt Kitchen“, developed by the architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky for all flats, is still well-known today, and considered a model example of the fitted kitchen. Of the 40,000 flats planned some 12,000 were realized. Yet only few labourers could actually afford them; they were usually occupied by members of the somewhat more prosperous middle class. New Frankfurt was one of the most prominent housing development projects of the twentieth century.

Many of its housing estates still exist today.

The Modernist Expansion under Ernst May in Frankfurt during the 1920s was one of the most important and influential episodes in the city’s (and even Europe’s) urban history. It marked Frankfurt as a pioneer of social housing, modern architecture, and urban planning.

Context

- Between 1890 and 1912, Franz Adickes, Mayor of Frankfurt implemented far-reaching urban planning changes. The city expanded outwards through annexations.

Overview map of Frankfurt am Main and surrounding area – Carl Ruppert – Frankfurt, 1913 – Line block print (reproduction), scale 1:20,000 Source: Historisches Museum Frankfurt , HMF.C26086 Adickes oversaw the construction of the ring road around the city, thereby promoting the further development of the adjacent districts.

-

During his tenure, Adickes confronted rapid urban expansion and the challenge of reorganizing land ownership for city development (roads, public spaces, etc.) without resorting to forced expropriation. To do so he introduced and refined the “Umlegungsverfahren” (land readjustment or land reallocation procedure) as a planning tool to redistribute irregular land parcels into usable lots while ensuring fair compensation among owners. Frankfurt’s Lex Adickes (the Frankfurter Umlegungsgesetz of 1902**) became a prototype for later urban land readjustment laws across Germany and also facilitated the New Frankfurt Urban Development Programme.

- After World War I, Frankfurt faced a severe housing shortage — tens of thousands of people were living in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions.

- In 1925, Ernst May (1886–1970), a modernist architect and planner, became Frankfurt’s city building director (Stadtbaurat).

- He launched the “Neues Frankfurt” (New Frankfurt) program — an ambitious plan to create affordable, healthy, and functional housing for the working and middle classes.

Source: Institut für Stadtgeschichte

Goals and Vision

Ernst May’s approach combined social reform, modern design, and rational urban planning. His key principles were:

- Functionalism: Buildings designed for efficient, healthy living — „form follows function“.

- Standardization: Prefabricated elements and modular design to lower costs and speed up construction.

- Green and open space: Integration of light, air, and greenery into every housing estate (inspired by the Garden City movement).

- Comprehensive planning: Coordination of housing, transport, schools, shops, and leisure spaces.

- Social progress: The aim was not just to build homes but to create a better way of living for all citizens.

Major Housing Estates (Siedlungen)

Ernst May and his team designed more than 15,000 dwellings across Frankfurt between 1925 and 1930 — a massive achievement for the time.

Notable examples include:

| Settlement | Location | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Römerstadt | Northwest Frankfurt (Heddernheim) | One of the first large-scale modernist housing estates; curving layout along the Nidda River; terraces and gardens. |

| Praunheim | Western Frankfurt | Affordable row housing for workers; strong use of standardization and repetition. |

| Bruchfeldstraße (Niederrad) | Early example (1926) | Compact, efficient housing with small gardens and communal amenities. |

| Bornheimer Hang | East Frankfurt | Innovative terraced layout on a slope; integration of landscape and architecture. |

Design Innovations

- Use of Modern Materials: Reinforced concrete, flat roofs, large windows, and clean geometric lines.

- Efficient Interiors: The famous “Frankfurt Kitchen” (by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky) — the world’s first fitted kitchen — designed to minimize housework and maximize hygiene.

- Color and Form: Collaborations with artists like Grete Schütte-Lihotzky, Mart Stam, and Walter Gropius brought Bauhaus aesthetics to Frankfurt’s social housing.

- Infrastructure Integration: Each settlement included schools, playgrounds, shops, and transport links.

International Influence

- The Neues Frankfurt became a model for modern housing worldwide.

- It influenced later public housing projects in Vienna (Red Vienna), Moscow (where May worked after 1930), and postwar New Towns in Britain.

- It was showcased internationally as an example of how architecture could serve social democracy.

End of the Program

- The project ended in 1930, when political opposition from conservatives and the economic crisis (Great Depression) halted funding.

- When the Nazis took power (1933), many of May’s team emigrated.

- However, the settlements survived and are still inhabited today — many are protected as heritage sites.

Legacy

Ernst May’s vision transformed Frankfurt’s urban structure and identity:

- It introduced the idea of urban planning as social policy.

- It set architectural standards for functional, humane housing.

- It made Frankfurt a laboratory of modern urbanism, comparable to Bauhaus or Le Corbusier’s works.

Would you like me to show you a map or diagram of the “Neues Frankfurt” settlements and their distribution across the city (with short descriptions of each)?

5. World War II Destruction and Postwar Reconstruction (1940s–1950s)

- Turning point: Devastation and the challenge of rebuilding.

- Key developments:

- Allied bombing destroyed over 70% of the city, especially the medieval Altstadt.

- Postwar rebuilding prioritized modern functionalist planning, not historical reconstruction.

- Development of wide roads and modern buildings in the city center.

- However, landmarks like the Römer were reconstructed in historic style.

6. Financial and Economic Metropolis – as compensation for not becoming Germany’s capital (1960s–1990s)

- Turning point: Emergence as Germany’s financial capital.

- Key developments:

- Construction of skyscrapers — start of the modern skyline (“Mainhattan”).

- Headquarters of the Deutsche Bundesbank and later the European Central Bank (ECB) located in Frankfurt.

- Massive urban renewal projects and transport modernization (U-Bahn, S-Bahn).

- Controversial redevelopment of Westend and inner-city housing protests in the 1970s.

7. Europeanization and Global City Era (1990s–present)

- Turning point: Frankfurt’s role as a global financial and transport hub.

- Key developments:

- European Central Bank (ECB) established (1998); new ECB Tower (completed 2014).

- Airport expansion made Frankfurt Europe’s busiest air hub.

- Reconstruction of the Altstadt (2012–2018) — “Dom-Römer Project” restored part of the historic city center.

- Current focus on sustainable urban development, housing crisis management, and riverfront revitalization (Mainufer).

8. Future Directions (2020s–onward)

- Turning point: Transition toward sustainability and inclusivity.

- Key trends:

- Green urbanism: Climate-adaptive urban planning, green roofs, and low-emission transport.

- Digital city initiatives: Smart infrastructure and data-driven mobility planning.

- Post-Brexit financial migration: Strengthening role as EU’s financial hub.

Would you like me to make a timeline diagram or map-based visualization showing these turning points and how Frankfurt’s urban form evolved over time?